As Riverdale Expands, Residents Hear Vision for New Southeast Roanoke Neighborhood

Residents asked how Riverdale development might address addiction and homelessness in Southeast Roanoke, and how affordable rents may be.

Apartments within walking distance of restaurants and the Roanoke River Greenway. Kayaking and rafting access. Art studios and food courts next door. Local businesses around the corner. Concerts on an outdoor stage. Pickleball courts! Riverdale sure sounds like a nice neighborhood.

Except that none of those perks exist, yet. Neither does the neighborhood. But work is underway to make Riverdale a reality, according to developer Ed Walker and the architects who presented the project’s most detailed plans yet before 40 people who gathered Sunday afternoon in Southeast Roanoke.

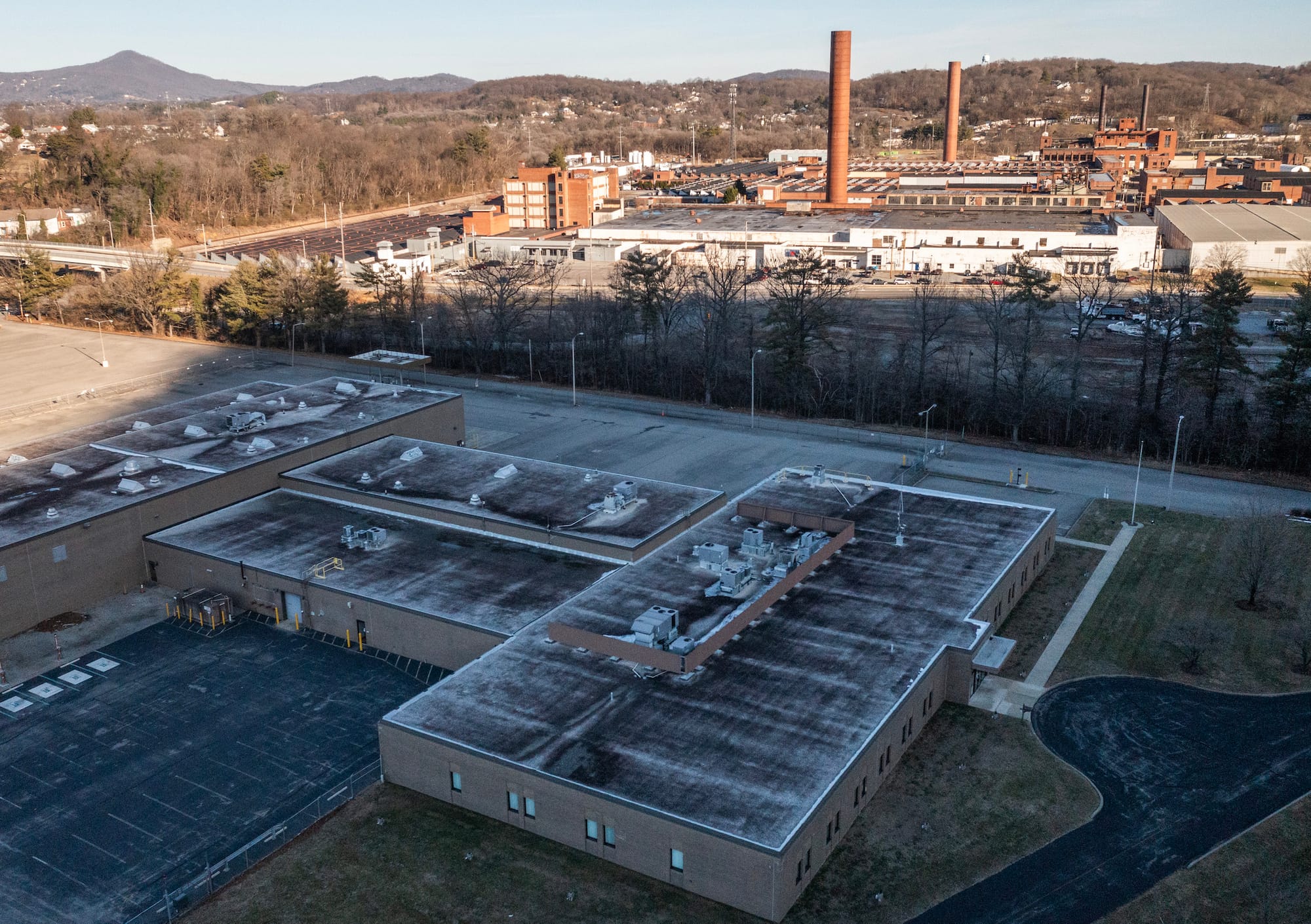

What they heard sounds like a complete transformation of one of Roanoke’s most historic industrial properties.

In one of the most ambitious economic development projects the city has tackled in decades, Walker is developing residential, commercial and entertainment spaces on the sprawling campus of the former Roanoke Industrial Center, where 89 tenants still operate businesses.

The property has been a business and manufacturing anchor in Southeast Roanoke for more than 100 years — dating back to the founding of the American Viscose company, which locals called the “silk mill” because of its production of synthetic rayon, and which employed nearly 5,000 people before closing in 1958.

Already, Riverdale is expanding. Walker and a partner recently agreed to buy 23 acres of a former AEP property on the other side of 9th Street. (He said the price will be made public when the sale closes this spring.) In total, Riverdale will include more than 120 acres, according to a planning application, which seeks to rezone the property as a “downtown” district to allow for “substantial use flexibility.” The initial phase will include a 260-unit apartment complex and an 85-unit “adaptive reuse project,” the application says.

The area is receiving renewed focus from city leaders after years of what local activists have perceived as benign neglect from city government.

Walker spoke directly to neighborhood concerns, and answered several questions from residents who live nearby during a nearly two-hour presentation.

Those questions included topics such as how Walker’s project might address substance addiction and homelessness problems that exist in Southeast Roanoke, and whether rents will be too expensive for some residents or business owners.

Walker said that he did not have detailed answers for some questions, but he noted that he has worked closely with neighborhood activists since the project was announced last year and that he wants to make sure people from the neighborhood will be able to take advantage of what Riverdale might offer. He called gentrification “a scourge” and said affordability is a project priority.

“If we fail to address the greatest needs and aspirations of Southeast,” Walker said at the beginning of the presentation, then the project as a whole “will have failed.”

Even as he and his co-presenters from the Richmond-based Baskervill design firm, projects architect Sonny Joy-Hogg and planner Melanie Smith, laid out grand ideas for what the development could become, Walker acknowledged that the project still faces many obstacles, most notably a massive environmental clean-up already underway of a site that has been home to heavy-polluting manufacturing for a century.

Walker said that “thousands and thousands of hours were dedicated last year” to clean up alone, adding that after crews had removed 2 million pounds of debris, “I stopped counting.”

Another problem is high moisture and water damage in most buildings, as Walker said that 90 percent of the structures are “not dry,” mainly due to poor roof conditions. Some buildings don’t have plumbing or electricity.

The project is moving ahead of schedule, he said, even as “we deal with devastating headaches on a weekly basis.”

Still, the presenters painted a positive picture of Riverdale’s future. Joy-Hogg and Smith compared the project to two other high-profile industrial neighborhoods that have been redeveloped in recent decades. The Brooklyn Navy Yard along the East River in New York City is a former shipbuilding base that is now home to smaller businesses, maritime industries and offices. Closer to home, and perhaps nearer to what Riverdale could eventually become, is Camp North End in Charlotte, North Carolina, where niche businesses, artists, small manufacturers, brewpubs and other entrepreneurs work on a property that once churned out Ford Model-Ts and Model-As in the 1920s and later built missiles.

Walker, who must invest $50 million into the project by 2040 with the city providing $10 million in performance-based loans that don’t have to be paid back if the project’s goals are reached, is hopeful that other collaborators will soon sign on to the project. Walker and nearly 100 other community members recently met with representatives of Artspace, the Minneapolis-based nonprofit that creates affordable living and working properties for artists. Artspace recently concluded a favorable feasibility study for Riverdale and is now conducting what it calls an Arts Market Study as it considers whether to join the project.

“I don’t want to jinx it, but I think we have a real shot at getting them to come,” Walker told the audience. “It would be wild if we get that done.”

Questions from attendees ranged from whether housing would be affordable to how Riverdale could help fight drug addiction in Southeast to what happens with more than 30 pieces of railway equipment stored on site.

Walker said that he hopes to keep rents affordable, especially for businesses, because the project’s costs and obstacles “are so vast, raising rents won’t help. … I am more about the ‘who’ and not the ‘how much.’”

He told a woman who asked about the railway equipment that those engines and cars are property of a historical group that will have to move them, eventually. Rail tracks that line the property must be removed this year, which will necessitate more environmental cleanup.

A local coach with the newly formed Roanoke City Little League baseball organization asked if a ball field could become part of the project. Walker said that if someone wants to propose how to do it, maybe someday it could happen.

Afterward, many of those who attended sounded optimistic about the project, with some sounding downright enthusiastic.

“I love it,” said Andrew Allegre, whose father leads a Spanish-speaking church in Southeast. Allegre, who owns a construction firm, said he hoped the project can provide housing for his employees, most of whom are Hispanic.

“It’s a good opportunity for growth, and I’d like to help find my guys a home.”

Laura Padgett, who has lived for 16 years on Morgan Avenue, just north of the industrial center, said she was excited about the project. Even though some attendees mentioned potential gentrification of Southeast among their concerns, Padgett said she welcomed the possibility of new people living and working in Southeast.

“I don’t know what gentrification, quote-unquote, means, but I am excited to see new people come to this area,” she said. “I think this is a great way to improve the Southeast area that’s seen so much blight and decline. Nothing will change unless we get new blood.”