Northwest Roanoke Residents Weigh In on Scaled-Back Eureka Park Recreation Center Upgrade

Roanoke is planning a $13 million upgrade of the recreation center, the largest spending project the parks department has ever undertaken.

James Lynch spent some of his happiest days as a kid in Eureka Park.

“I played basketball in the morning, and I played baseball every summer,” Lynch said. “I was there when they cut the first trees for the building.”

That would have been in 1965, when the Eureka Park Recreation Center opened as the centerpiece of one of Northwest Roanoke’s most popular parks. Now, 58 years later, the rec center and the park don’t get used the way they did when Lynch was young.

The recreation center has been open only a few hours daily since the Great Recession of 2008 zapped a hole in Roanoke’s Parks and Recreation Department budget that has never been filled. Mostly, it’s used just a few hours a day for childcare programs. Kids don’t play as much baseball and softball on the grassy fields as they did a couple of decades ago, when the hilly emerald isle of Northwest Roanoke hosted ball games, picnics and numerous community activities.

Now, though, Roanoke plans a $13 million upgrade of the recreation center and some of the surrounding grounds as part of the largest spending project the parks and recreation department has ever undertaken.

Still, many residents who live near the park, which lies north of Staunton Avenue between 14th and 16th Streets in a predominantly Black neighborhood, have concerns about the project, which has already been scaled back due to rocketing construction costs.

A proposed brand new, 30,000 square-foot recreation center was dropped in favor of renovating the existing 10,000 square-foot building and adding a new 6,000 square-foot wing. Some older residents lament the loss of the ball field, which will become a common park area for large events, such as the Juneteenth celebration which was held in Eureka Park on June 17. Some people have reservations about gender-neutral bathrooms and want more security cameras installed throughout the park.

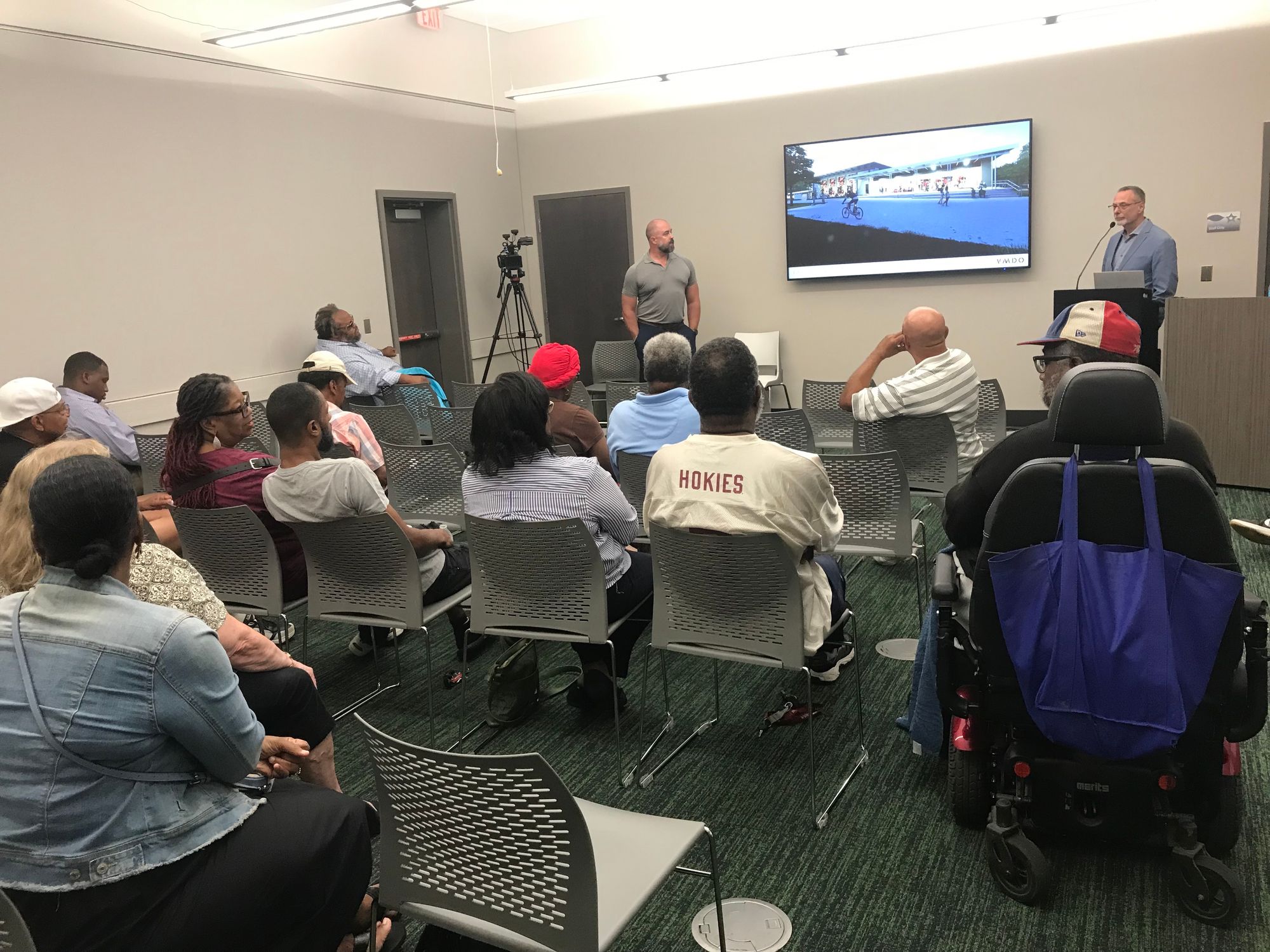

About 20 people aired their concerns to parks and recreation director Michael Clark and architect Joe Celentano during a community informational meeting at the Melrose Branch Library Tuesday night, the latest in a series of public sessions about the project.

Most of the attendees remembered the recreation center from its earliest days in the 1960s and ’70s, and they longed for a return to a time when families regularly used the facility.

One man said that a softball field would draw families to the park for games. Clark said that the rec department replaced the field with open space after residents at other meetings said they preferred a different kind of recreational space. He pointed out that the ball field at Horton Park, about a half-mile from Eureka, is being used again for baseball teams.

One woman did not like the plan for 10 individual bathrooms that can be used by any gender. That design features single toilets with locked doors that are accessible through a common area that includes a sink and water fountain.

“I don’t see it being safe,” the woman said. “There’s more predators out there … You can go in if you’re male, female, dog, cat. I’m not comfortable with that.”

Clark said that he didn’t see the gender-neutral bathrooms as being unsafe, especially because individual bathrooms are completely enclosed and near an area where other people are around. Also, most new city structures require gender-neutral bathrooms, he said.

“Bad things can happen regardless of what we do, but this design makes things as open and safe as possible,” he said.

As for safety, the current design calls for two video cameras to be installed near the front doors of the recreation center. Some residents wanted cameras in other places throughout the park, even in areas that will be lighted until 10 p.m., such as the basketball court and a new walking trail.

As for other high-tech requests, Anthony Smith, a local businessman, told Clark and Celentano that adding Wi-Fi to the rec center would benefit residents, especially nearby households that don’t have easy internet access. Currently, no Roanoke park has Wi-Fi.

Even as people peppered Clark and Celentano with ideas, the renovation timeline appears firm, especially as the clock ticks down on the required spending of pandemic relief federal funds dedicated to the project.

The city is using about $8 million of federal funds from the American Rescue Plan Act, a law passed in 2021 that sent $1.9 trillion to localities to help with economic recovery during the pandemic. Those funds must be allocated before the end of 2024, Clark said.

The city is providing an additional $5 million for a project that started with a $9 million budget but exploded as inflation caused construction projects to rise. Clark said that if the Eureka Park renovation had started in 2019, it could have been completed at about $300 to $400 per square foot. That cost is now nearly $700 per square foot, he said.

Celentano, a principal partner with Charlottesville-based design firm VMDO, said that he believes that most cost projections are leveling, which gives him hope that the project can be completed with the current budget.

Even so, the current plan is scaled back from early designs. The 1965 building, which was slated for demolition, will remain. Celentano told the audience that the current center was built with prefabricated concrete, which means that the structure is solid, even if the mechanical guts, which include HVAC and electrical systems, will need to be replaced.

By the end of the meeting, most of the attendees seemed to be hopeful that the changes would be good not only for the park but for the surrounding neighborhood.

After the Eureka Park presentation, a few people stayed to hear plans for another Northwest Roanoke Park — the newly named Estelle McCadden Park, formerly Kennedy Park.

That park, renamed for a longtime civil rights and community activist, has mostly been a large grassy area with few amenities.

Katie Slusher, parks and recreation’s planning and development coordinator, told attendees about ideas for adding playgrounds, walking trails and picnic areas, which received the most support afterward when people chose their top priorities for improving the park.

As for Eureka Park, Lynch, who recalled playing basketball as a kid and later coaching teams there, suggested the entire park could be renamed for Joseph Brown and Barbara Kelley, two people who operated the rec center in the 1960s.

“What was Eureka named for anyway?” he asked during the meeting. “A slave owner?”

Eureka Park takes its name from the Eureka Land Company, a development firm started by Virginia and West Virginia coal barons more than a century ago to construct housing and parks on the outer edges of the railroad boomtown of Roanoke. Even though the area has been predominantly an African-American neighborhood since the 1950s and ’60s, before then it was mostly a white working-class enclave at the end of the streetcar line, in the woody suburbs a few miles from the sooty downtown clouded by smoke of coal-burning steam trains and the East End Shops that churned out rail engines and cars.

During the urban renewal era, when Roanoke paved over Black neighborhoods near the current Berglund Center and when white families fled to the burgeoning cul-de-sacs of Roanoke County, the Northwest quadrant of the city became a cauldron of Black life.

That’s why what happens to Eureka Park and the Lyndon Johnson-era rec center are important to the community.

“It’s an important conversation,” said Smith, one of Tuesday’s attendees. “They need to think about more than sports. They need to think about Wi-Fi and things that will help all families. The entire area can be as strong as it used to be and even better.”