Gainsboro Residents Urge City To Focus on Present Housing Stock Over Future Hub

Residents expressed confusion and criticism over a report aimed at guiding the long-neglected neighborhood’s revitalization.

Gainsboro residents expressed confusion and criticism over a report presented Tuesday aimed at guiding the long-neglected neighborhood’s revitalization.

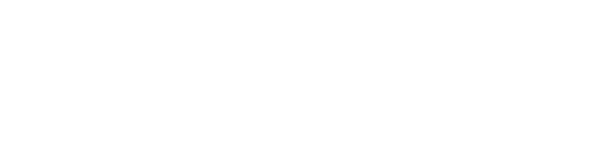

The study from a Richmond-based consultant says Roanoke should focus on rebuilding the kinds of shops, restaurants and offices that once lined Henry Street; establish a healthcare center and a grocery store near the former Claytor Clinic; and develop a community center and housing along Jefferson Street.

“Gainsboro was torn apart by urban renewal, and now it's time to honor that while at the same time coming up with priority areas and priority projects,” said Chuck D’Aprix of the consulting firm Downtown Economics, which recently finished neighborhood center plans for other areas across Roanoke.

Yet several current and former Gainsboro residents at the Gainsboro Library Tuesday urged the city to fix up the area’s dilapidated houses before embarking on any shiny new projects.

“To me, you’re doing it backwards,” resident Joyce Bolden told D’Aprix and city officials. “Until you clean all that up, I’m not interested in anything you build here.”

The city has earmarked $5 million in federal pandemic relief funds for a Gainsboro hub centered on healthcare and small business development. The report is designed to help guide the city’s decision-making on how to carry out a revitalization of the predominantly Black neighborhood.

“If you're talking about redeveloping a neighborhood, it's got to be housing first,” said Gayle Graves, whose mother grew up in Gainsboro. “That’s the concern here.”

Residents expressed wariness that some of the amenities floated as possibilities in the report — an amphitheater, yoga studio and coffee shop among others — aren’t meant for neighbors but for downtown visitors.

“It’s easy for them to walk across the bridge and have a lovely weekend,” Bolden said, “and it’s not intended for us.”

Graves recalled passing out flyers for her church before the pandemic to houses on Gilmer Avenue. She said many were vacant, owned by corporations that weren't fixing up the buildings or renting them out.

“They are waiting,” she said. “This kind of helps me understand what they are waiting on.”

City officials and D’Aprix insisted they want to hear what the community wants for Gainsboro. The 60-page “Community Hub Concept Plan” was the result of an earlier community meeting and survey results from 77 citizens. Copies of the report weren't available at the meeting. Officials told attendees it was online at the economic development office's webpage but a reporter could not find it there Tuesday night.

While the study outlines how the city could carry out major ideas, like a health center hub and grocery store, D’Aprix noted the report also advocates for “small, doable items that can be done incrementally.”

Those range from improving crosswalks, to installing neighborhood banners on new decorative lamp posts, to fixing the facades on existing buildings.

And the plan acknowledges that parts of Gainsboro’s current landscape impede growth.

“Vacant lands and boarded up buildings have given way to barren, unattractive, and nearly deserted streets which has allowed homeless encampments to surface ... all of which is eroding the community fabric and connection,” says the report, a copy of which The Rambler obtained from the city.

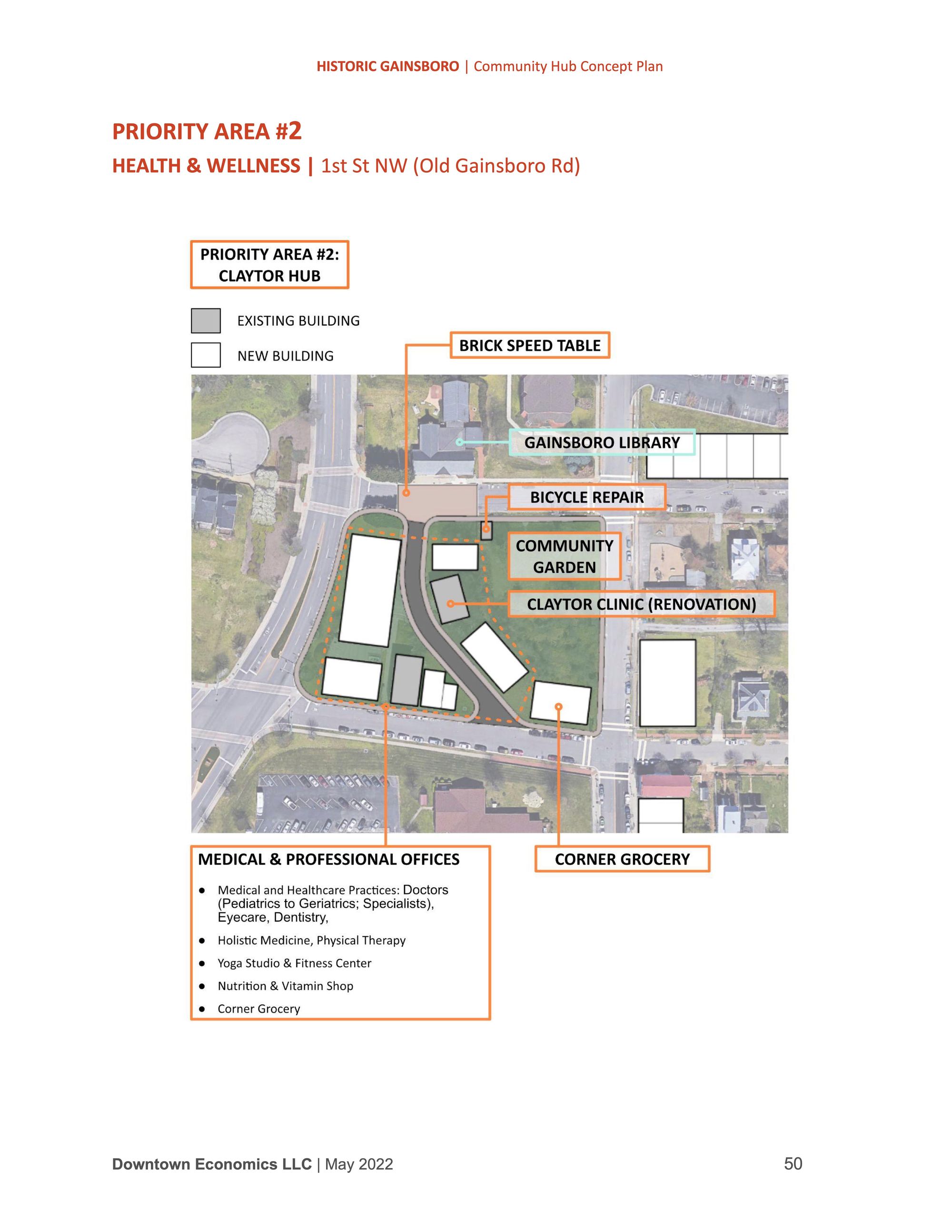

The study also says Roanoke should leverage the history of the Claytor Clinic for a health and wellness center. Last fall, the city tried to buy the property from the owner for the promised Gainsboro community hub, but the deal fell through.

“The medical, health and wellness activities and individuals that operated in this space were trailblazers and history-makers for both what they risked and for what they created,” the report says. “Given the history, proximity to public facilities (like the Library and Head Start) and centrality to residential (homes / senior living facility), this block is the ideal location for neighborhood scale redevelopment and infill development to create a health and wellness neighborhood center across a spectrum of interests, initiatives and entities including” doctors offices, a fitness center, a yoga studio and a corner grocery store.

Gainsboro was torn apart during urban renewal, during which, from the 1950s through the 1980s, the government seized land for development. Much of that did not occur, while the neighborhood to the east was leveled and replaced with Interstate 581, Berglund Center and commercial buildings. Distrust of the city and its intentions remain.

“What is it about? Building an area that is generating revenue for the city, when people are sitting here telling you that this neighborhood is falling apart, these houses are falling apart, and we’re still thinking about moving forward with this?” said Phazhon Nash, who sits on the city’s citizen Equity and Empowerment Advisory Board. “This is the exact reason why people have a mistrust — honestly, no trust — and such a poor relationship with Roanoke City.”

The plan is hardly the first report outlining how the city could breathe new life into Gainsboro.

In 1984, Mayor Noel Taylor called for a revival of Henry Street during his State of the City speech. Three years later, an article in The Roanoke Times & World-News wrote about the results of a plan proposing a revitalized neighborhood.

“Consultants have developed a $3 million restoration plan that calls for the music center, five restaurants, convenience stores and rental space for professional offices,” the story said. “The plan also calls for construction of a public plaza, new street lights sidewalks and landscaping.”

In 1987, Roanoke’s housing authority bought 20 properties — and condemned seven others when owners refused the agency’s offer — for construction that never materialized.

By 1996, city leaders and residents were still debating what to do with the neighborhood. Newspaper stories recount heated public meetings over plans to “turn dilapidated Henry Street into a jazzy tourist mecca,” at a cost of $18.5 million in the vein of Memphis’s Beale Street.

None of it happened.

Residents rejected the plan and came up with their own, a railroad-themed project that mostly fizzled. Eventually, the only major developments that emerged were city-led initiatives: a parking garage, the Roanoke Higher Education Center and upscale apartments in the former Norfolk Southern headquarters.

Wayne Leftwich, assistant to the city manager, said the next step would be for the concept plan to go before City Council for acceptance.

“I'm not sure why this is going to City Council [when] you’ve got people here in the community who are saying, ‘Hold up,’” Graves said.

Leftwich said city officials will continue to engage with residents about what parts, if any, outlined in the report will come to fruition.

Hanging overhead is a December 2024 deadline by which the $5 million in federal pandemic money must be set aside for specific Gainsboro projects.

Several attendees urged the city to begin spending some of the money on beautification efforts. Resident Jordan Bell, who leads history tours of Gainsboro, floated the idea that a coalition of residents — in the form of a neighborhood nonprofit — could be the recipient of the funds and spend it to residents’ wishes.

“I think the plan is great for a neighborhood center, but as we heard tonight, housing is the biggest issue in this community,” Bell said. “I think we need to continue some type of infrastructure that controls the resources that come into this community. If we don't, this community is going to look a lot different in the next 10 years than it does right now.”