Once Site of Roanoke's Dump, Washington Park Haunted By Legacy of Environmental Racism

As Roanoke plans major upgrades to Washington Park, tensions linger over the city's history of urban planning in majority Black neighborhoods.

Rats seen scurrying through school building corridors. A noxious odor permeating the nearby neighborhood. “This is the kind of thing from which social riots are made,” the Reverend James A. Allison warned members of the Roanoke City Council in 1963. His anger was focused on the municipal garbage dump then located in Washington Park in the heart of Roanoke’s segregated Black community.

“You had Black people at Lincoln Terrace, children, getting ill,” recalled Nathanial Benjamin, grandson of the Reverend R.R. Wilkinson, who was then the president of the Roanoke chapter of the NAACP. “They had to go through [the dump] to the schools, to Lucy Addison.” Sixty years later, Benjamin said he believes these children, who are now elderly, have “developed respiratory problems because of living in that dump area. Some of them have asthma.”

As the city plans to unveil major upgrades in Washington Park, including a new swimming pool set to open this summer, tensions linger over the history of Roanoke’s approach to urban planning in predominantly Black neighborhoods. From Washington Park to Evans Spring, the city has long targeted open spaces in Black residential communities for the siting of garbage dumps, highways, and big box stores.

There is a term for this, Benjamin said — environmental racism.

A park for Black Roanoke

A 1909 document, the city’s first comprehensive plan, bemoaned the desecration of green spaces in Gainsboro, just south of today’s Washington Park, noting that what “was originally beautiful rolling country with high hills and deep valleys” is now “dotted over with ramshackle… cabins that hang insecurely on the side hills.” The plan recommended that open space be allotted, on the north side of the city, for a public park.

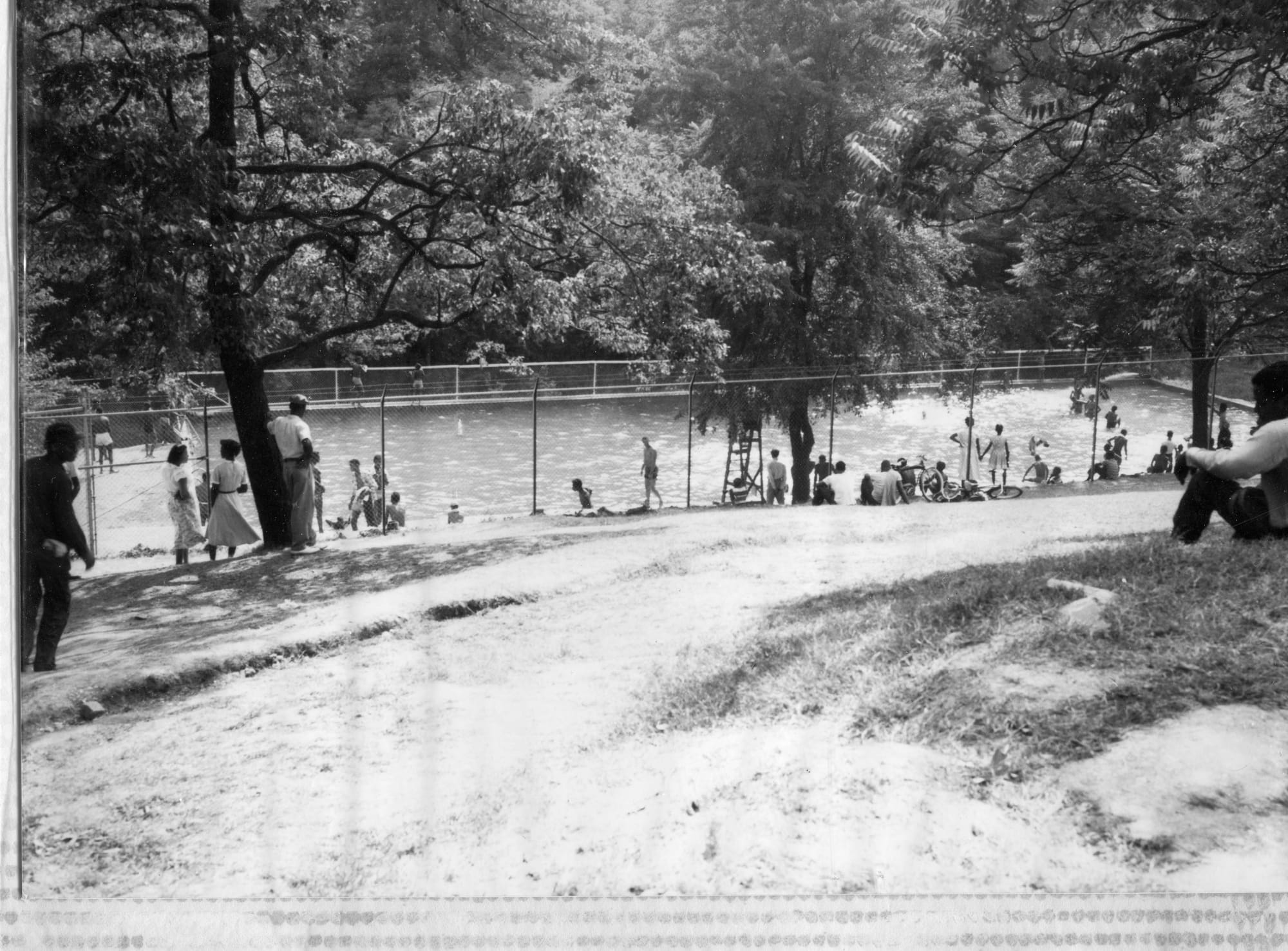

There was a racial dimension to the city’s first efforts at parks development. While Highland Park and Elmwood Park were developed on the south side of the city in predominantly white neighborhoods in the early 1900s, it wasn’t until 1922 that the city began purchasing private lots north of Gainsboro for a park that would serve the city’s Black community. Washington Park, on a smaller footprint than today’s current park boundaries, opened to the public in 1923.

During the Jim Crow era, it was private parks designed and run by Black entrepreneurs, however, that drew the greatest crowds among Roanoke’s Black population. Alongside what is now Orange Avenue, near the present-day YMCA Express building, an amusement park for Black Roanokers called Dreamland operated in the 1930s and 1940s, while up above Washington Park to the north, near the present-day Lincoln Terrace Elementary School, Springwood Park operated a pool and a dance hall.

In oral histories conducted with Gainsboro residents in the 2000s, narrators recalled enjoying the amenities of these businesses. “When you got to Washington Park, they had the swimming pool and the dance hall over there and there were a lot of picnics in Washington Park. People came from everywhere on Sundays and holidays to have picnics in Washington Park.” Another long-time resident noted “during the time of segregation, we had Black people coming from Lynchburg, Bedford, and everywhere else to go to Washington Park.”

But by the 1940s, these amenities were threatened by the city’s decision to begin using Washington Park as a municipal dumping ground.

Civil Rights Movement rallying cry

By the turn of the 1960s, the conditions surrounding the Washington Park dump were “just horrendous,” Benjamin said. One long-time Roanoke resident told Benjamin that his father went around “forming rifle clubs just for the rats, to kill the rats, to get the rats out of the neighborhood.” Others recalled the frequent fires caused by “gas fumes from the dump,” and even dead rats found in the park’s swimming pool. “I guess it just made the people to where they had had enough. They wouldn’t take no for an answer.”

The Civil Rights movement in the South is often remembered in stories of school integration, bus boycotts, and lunch counter sit-ins. Yet there was another dimension to Civil Rights activism: the fight over environmental racism.

The targeting of Black communities for municipal dumping was “really prominent in the U.S. South because of structural racism,” said Mary Finley-Brook, a professor at the University of Richmond and an expert in environmental justice. Governments and corporations are “able to really use their power to lobby and make sure that when dumps get sited, they’re being sited in areas that are vulnerable.” Finley-Brook noted that as small municipal landfills like the dump at Washington Park were ultimately shut down, cities such as Roanoke started shipping their waste off to larger “mega landfills” across the state that have continued to be sited in poor and disadvantaged communities.

Washington Park was not the only site in Roanoke that was once a dumping ground. Katie Slusher, park project manager for the city, explained there are at least three current “landfill parks” in the city of Roanoke, meaning a park that is built, at least in part, on top of a former landfill: Washington Park, Fallon Park, and East Gate Park.

Yet Washington Park is notable for two reasons: it was the city’s main dumping ground in the historically Black Northwest quadrant of the city, and it became a rallying cry for the city’s burgeoning Civil Rights movement. In the early 1960s, Black activists in Roanoke had achieved some successes with the peaceful integration of several downtown lunch counters and a few elementary schools, yet the broader work of widespread racial integration remained unattained.

Wilkinson, the pastor at Hill Street Baptist Church and head of the city’s NAACP chapter, was particularly attuned to the shifting pulse of the national Civil Rights movement. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s Birmingham campaign in the spring of 1963, the source of his famous “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” had a major impact on Roanokers’ views of the Civil Rights movement. They watched television footage of young Black activists mauled by police dogs and attacked with high-pressure fire hoses.

Wilkinson saw an opportunity, amid King’s activism, to put pressure on Roanoke’s mayor and City Council to close the dump. His ally, Rev. James Allison, a white pastor at the predominantly white Raleigh Court Presbyterian Church, warned City Council in May 1963 of “Birmingham-type” demonstrations in Roanoke if they did not shut down the dump.

“My grandfather always had a Plan B,” Benjamin said. “And he told the City Council that if you don’t get that dump moved out by a certain date… that he will lead a group of mothers with their babies and carriages down to Washington Park, and he’ll form a human chain to block the dump trucks from entering. … And so you can imagine the faces of the City Council members, right?”

One week prior to Wilkinson’s deadline, the City Council voted to shut down the garbage dump, forestalling Wilkinson’s proposed “baby carriage brigade.” To the dismay of the mostly white residents in the city’s East Gate neighborhood, the city began shifting municipal waste immediately into an area alongside Tinker Creek (today’s East Gate Park, another landfill park).

'Suspected legacy' of contamination

The dump at Washington Park was immediately covered with “construction dirt” from the excavation of Interstate 581, and later, in the 1970s, a new swimming pool was built directly adjacent to the former landfill. That pool was demolished in 2023 after the city discovered numerous structural issues related to the site’s environmental legacies.

“It was leaking water substantially,” Slusher explained. After demolition, the city conducted soil borings on the former pool site and concluded that “[landfill] material had migrated underground in such a way that it had affected the soils underneath where that pool was.”

Slusher said the ground there “is not like normal soil” and it cannot support “anything that requires foundation work.” Even playing fields are not suitable on top of the landfill because of the danger of “soft spots” where the earth can cave in and form a divot. This explains why the football field at Washington Park is located on the edge of the park, not over the landfill.

Today, a new pool is under construction closer to the original site of the Dreamland pool and amusement park on the lower half of Washington Park. Residents fought to shift the location of this pool’s construction to preserve a nineteenth-century caretaker’s house that they argue is one of the last undisturbed vestiges of Washington Park’s Black history. The city has not announced any plans for the cottage. The parks department, Slusher said, is working with artists on a mural project that will adorn the new pool house building, scheduled to open this summer. While they are still “cooking up ideas,” Slusher hopes the mural will in some way reference Dreamland, part of the area’s neglected Black history.

Another commemoration of the park’s history was made in 2023 when a street that cuts east-west through Washington Park, passing immediately adjacent to the former landfill, was renamed in honor of Wilkinson.

“I think he would be actually pleased and not pleased at the same time,” Benjamin said. “You know, just the dump is basically not here today, right? However, apparently there’s still something there. Maybe they didn’t do as thorough a job of cleaning up that dump as we thought.”

In fact, a report released in 2024 by the city’s stormwater division mentions Washington Park, East Gate Park, and Fallon Park as sites of former landfills with a “suspected legacy” of PCB contamination, or polychlorinated biphenyls, a dangerous chemical that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency deems a “probable human carcinogen.”

Urban landfills, Slusher explained, generally do not get cleaned up. Instead, they are capped and turned into green spaces. And the garbage that was buried there remains, forever, in place.

Landfill parks can “continue to off-gas for sometimes twenty or even thirty years,” Finley-Brook said. “And so, if you don’t necessarily know what was in it, you’re not going to necessarily have a sense of just how much toxicity it will produce.”

Future development of Washington Park will be determined through a major planning process that will be announced in the coming months, Slusher said. “We’re going to be looking for a huge amount of input on that planning process for the park, and so I just want to shout it from the rooftop” that community members should get involved. Part of that process may involve grappling with the legacies of environmental racism here, and charting a path forward for the future of Northwest Roanoke’s historic park.

Correction (3/12/25) — An earlier version of this story misstated the church affiliated with Rev. James Allison. It is Raleigh Court Presbyterian Church. We regret the error.