Residents Near Roanoke's Evans Spring Say 'No Development.' The Property Owners and City Have Other Ideas.

“The ‘no development’ option is not really an option that’s on the table,” a city official says.

A couple weeks ago, at a Northwest Roanoke church down the road from a vast swath of woodlands called Evans Spring, nearby residents sang from the same choir book.

There should be no development of the 150 acres across the interstate from Valley View Mall, they said.

But the property owners, and City of Roanoke, have other ideas.

For decades, the owners have tried to attract a developer to turn the long-vacant land into a complex of stores and apartments. But ideas to develop the properties have fallen through after community pushback.

Now the city has commissioned a master plan to guide future development. And despite neighbors’ concerns, the city and the property owners says “no development” is not an option.

“It does conflict with the residents, but there's a reality that the residents don't understand and can’t understand, and that is the larger picture,” said Peter Cooper, a consultant to Heritage Acres LLC, a Washington, D.C. company that owns 28 acres of Evans Spring.

“Sure, I would love to have all the land around me just as beautiful and undeveloped as possible,” he said with a chuckle, “but that's not reality.”

Last summer, Roanoke City Council unanimously agreed to come up with a master plan for what the city describes as “the largest assemblies of developable vacant land left in Roanoke.” The city, Roanoke’s Economic Development Authority and three of the four property owners collectively put up $225,000 for the plan.

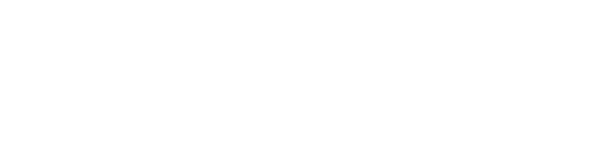

Earlier this month, city consultants held the first large-scale community engagement meeting to hear residents’ ideas for the land. About 120 people turned out at Williams Memorial Baptist Church. After conferring in small groups, one after the other, residents urged city leaders to leave the land alone.

Chris Chittum, the city’s planning director, described the feedback as “disappointing.”

“I think all of them pretty much indicated they would not want to see any development. … And to be forthright about it, that’s not really the input that we were looking for,” he said. “The ‘no development’ option is not really an option that’s on the table.”

The neighbors

At Williams Memorial, raw emotions were on display as residents expressed mistrust with city government and invoked Roanoke’s history of urban renewal.

Evans Spring borders the predominantly Black neighborhoods of Melrose-Rugby, Fairland and Villa Heights. Several families relocated there after the city used eminent domain in the 20th century to seize homes in Northeast Roanoke.

Michelle Gaither spoke about how Berglund Civic Center now stands where her grandparents “and a whole lot of other people in this room” used to live.

Beginning in the 1950s, the city paid pennies on the dollar for Black families’ homes, bulldozed them and ran a highway through the city. Thousands of families were uprooted and forced to move.

“We have absolutely no interest in repeating that whatsoever,” Gaither said.

While the property at question is private — and city officials say eminent domain will not be used — fears around gentrification and displacement remain.

“We would like for this to be preserved. We don't want to see anything happen with this land,” resident Courtney Smith said. “And we would like for Roanoke to consider the past and history of its Black residents.”

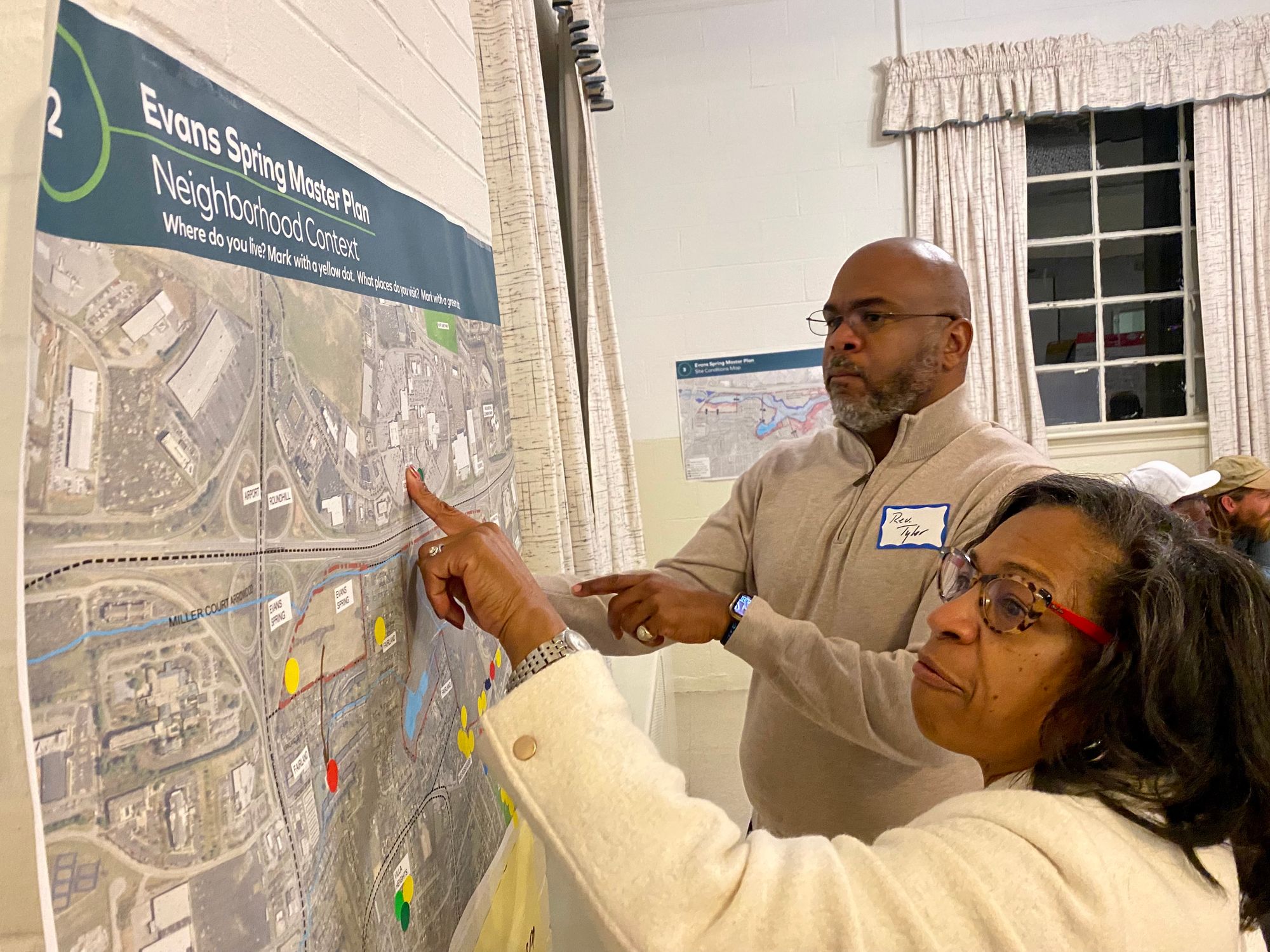

Residents told the city consultants that they want to keep the character of the adjacent single-family-home neighborhoods and protect the waterways and wildlife that make up Evans Spring.

“The people who own the land, that they want to bring in commercial development, I can almost guarantee that where they live, there’s no commercial development,” said Kierra F., who, in declining to give her last name to a reporter, said she is an outspoken business owner and did not want to be “targeted.”

“They want to come here and shop and bring noise and bring a lot of confusion and then go back to their quiet home and enjoy their wildlife,” she said. “I don't understand how, as a human being, you can sleep at night when you want us to do something that you would not do yourself.”

“Amen!” someone shouted.

Ryan Bell, a community advocate who works in education, said the questions on the consultant’s survey “trouble me deeply” because they seemed design to lead residents to approving development.

“And so, Question three, ‘How can the space on this site benefit the community?’” Bell said. “It already is!”

“If you've been listening, everyone's saying the same thing,” said resident Phazhon Nash, who sits on the city’s Equity and Empowerment Advisory board. “This community, this neighborhood, people who have an interest in this community and in this neighborhood, are all echoing the same sentiment. The answer is no.”

Theresa Gill-Walker, who has spoken before City Council in recent months about Evans Spring, said: “We are David. They are Goliath. And y’all know how that turned out.”

At the end of the community meeting, Bill Mechnick, president of Land Planning and Design Associates, Inc., which is designing the master plan, said there exists a “reality” that is a “tough problem” to solve.

“We're trying to combine the raw fact of property ownership, that different folks own this property and would like to sell it … and community needs and values,” he said. “So if there's a way to figure out how to accomplish both those things, then great. If there's not, the thing’s dead in the water.”

Some residents suggested the city buy the land and turn it into a stormwater retention park and nature preserve.

Mechnick said that might be possible — if the city thought it feasible. (Chittum later said it is not.) He said his team’s role will be to present to City Council “what viable options are” for the land.

Chuck D’Aprix, a community engagement consultant, told the crowd that he would amend the survey so that there would be a “no development” option.

“The vast majority of surveys we’ve gotten that I’ve looked through say ‘no development’ anyway, so people have figured out a way to put that on the survey,” he said.

D’Aprix said the next step would be small meetings with neighborhood associations and faith groups. Some residents said there was no point in talking about the issue further.

“What they’re doing here is morally wrong. And we’re going to fight,” Kierra said before walking out. “We’re done with meetings. I’m not attending any more meetings.”

The owners

Across 150 acres of woodlands, 125 individual parcels and a handful of corporate entities, four owners control Evans Spring.

They are Ed Laios, a Washington investor who owns parcels through Heritage Acres LLC; Anderson Wade Douthat IV, whose firm Allegheny Construction Co. purchased land beginning in the 1990s; the Huff family, who used to operate a dairy farm along the highway; and Joe Walker Ramsey, whose family grew vegetables on 19 acres off Hershberger Road.

None of the owners are developers.

Douthat did not respond to phone calls and emails left over multiple weeks. A representative of the Huff family also did not respond to messages.

In 2019, Ramsey convinced a North Carolina developer, Pavilion Development Company, to take an interest in the properties.

Since most of the land is zoned as agricultural, any major development would require a rezoning, which is approved by the city’s planning commission, then City Council.

Pavilion proposed 300 apartment units spread across 14 buildings, an office building, a wholesale warehouse club, a restaurant and a golf-related recreational facility. Speculation at the time was that Topgolf and Costco would be a part of the complex.

As part of the development, Pavilion would have bought 16 homes — an arrangement that residents say dredged up the ghost of urban renewal.

A month before the pandemic, however, Pavilion withdrew its plans, citing skepticism expressed by the city’s planning commissioners, who are appointed by City Council.

Cooper, who was involved in the talks with Pavilion on behalf of Heritage Acres, said the developer had a roughly $20 million option on the properties and had already spent $1 million on various engineering and planning approvals.

“They walked away from it,” he said. “So I don't know what the compromise is going to be on this go-around.”

(At the community meeting, Mechnick, the city consultant, panned Pavilion’s proposal. “I saw that last plan, it was disgusting,” he told residents. “I mean, it looked like somebody who designed industrial parks did the development.”)

Residents say they want to protect the trees and waterways that make up Evans Spring. PHOTOS BY DON PETERSEN FOR THE ROANOKE RAMBLER

But Cooper believes any future development must include large commercial stores like those across the interstate at Valley View.

“Everybody knows you have to have big boxes to make any kind of commercial development in today's market successful, especially ones of this size,” he said.

Cities aren’t keen on residential developments because they don’t generate as much in tax revenue, he said. Especially residences with children, which put a burden on school resources.

“Senior housing,” he said, “is very appealing to most communities because there’s no pressure on schooling and stuff like that.”

That philosophy also leads him to believe it’s unlikely the city will buy the land.

The total value of the land is assessed at $3 million, according to a Rambler data analysis of property records. But as Pavilion’s $20 million option indicates, the properties could fetch far more.

“I wouldn't think that the city has that kind of money to throw around and then build a park,” Cooper said.

Ramsey agreed.

“I don't think for a minute the city's just going to buy all this land, and not do anything with it,” he said. “I mean, that’d be foolish. I don't want my tax money spent that way.”

Interest in developing Evans Spring gained steam a decade ago after Virginia agreed to finance the completion of an interchange at Valley View Boulevard, making the site theoretically accessible to highway traffic.

In 2013, the city adopted the “Evans Spring Area Plan,” which states that the land “is best suited to mixed-use development and, specifically, a mix of residential and commercial development.”

The plan notes that much of Evans Spring lies in a flood plain and recommends framing development around Fairland Lake and Lick Run. The Lick Run Greenway also zigzags through a portion of Evans Spring.

Beginning 70 years ago, Ramsey spent summers at his family’s farm picking onions and squash. They would sell two truckloads a day to Kroger and Mick-or-Mack.

Nowadays, the field lies fallow. He leases the land to a man who mows it for hay. While Ramsey is not formally a part of the city’s agreement with property owners, he supports the effort. He believes development is only a matter of time.

“People hate change, as a rule, and I understand that,” Ramsey said. “But it’s going to happen someday.”

The city

Then there are the politics.

While city staff are proceeding with a master plan to guide development, some elected officials have expressed wariness with the idea of developing the land in the first place.

And it will be up to City Council to decide whether a development proposal should proceed.

The future of Evans Spring emerged as a campaign issue in last year’s City Council race. At a candidates’s forum in Northwest Roanoke last October, 10 candidates said they would not support redeveloping Evans Spring for commercial purposes.

“Do you support the rezoning and development of the Evans Spring area for business?” moderator Raekwon Moore asked. “Yes or no, and why?”

“No,” Vice Mayor Joe Cobb said. “I do support residential, because I think we need more homes, new affordable homes, but I think they have to align with the neighborhood.”

“I don't support the development of business, but I do support residential because we do need the housing; we need affordable housing,” Councilwoman Vivian Sanchez-Jones said.

“No,” Councilman Peter Volosin said. “I think our priority should always be to see what we can redevelop first.”

Councilman Luke Priddy said no, and noted that since the November election would determine a majority on Council, a majority is opposed to commercial development.

“That means that this is not going to be rezoned for business as long as anyone up here is elected,” he said.

D’Aprix, the city’s consultant on community engagement, said he expects to wrap up the public feedback portion of the master plan by May. Shortly thereafter, Mechnick’s team will present more concrete ideas, including drawings of development options.

Chittum, the assistant city manager, said there is so far no indication that City Council has changed its policy on Evans Spring, which he said goes back to the 2013 area plan.

“Develop or not develop has already been decided,” he said. “If folks think we’re going through this process to not develop the property, then I think that’s not very observant.”

Correction (2/16/24) — A previous version of this story with a quote attributed to Vivian Sanchez-Jones was written incorrectly due to a transcription error. The corrected quote reads, “... we do need the housing; we need affordable housing.”