Strand Theatre Revival Brings Music Back to Henry Street

On Saturday, Gainsboro advocates will celebrate the old Strand, the Ebony Club and other Henry Street entertainment landmarks with music, stories and food.

Woodrow Walker remembered when the lights came up and the dancing girls hit the stage at the old Ebony Club.

Walker was a keyboard player and singer with the Chevies and Premiers, one of Roanoke’s most beloved rhythm and blues bands of the 1960s and a regular at Henry Street nightclubs in the mostly Black neighborhood of Gainsboro.

The band launched into popular R&B hits of the mid 1960s — “Shout” by the Isley Brothers, the Temptations’ “My Girl” were big favorites — as the ladies danced on the stage, and club patrons sat at tables and dined on pickles and hot smokes and sipped whiskey from bottles they brought themselves.

“It was a floor show like you’d see in New York City or Washington, D.C.,” said Walker, now 87 and a retired Baptist minister in Franklin County. “Henry Street was a popular place back then.”

That was more than 60 years ago.

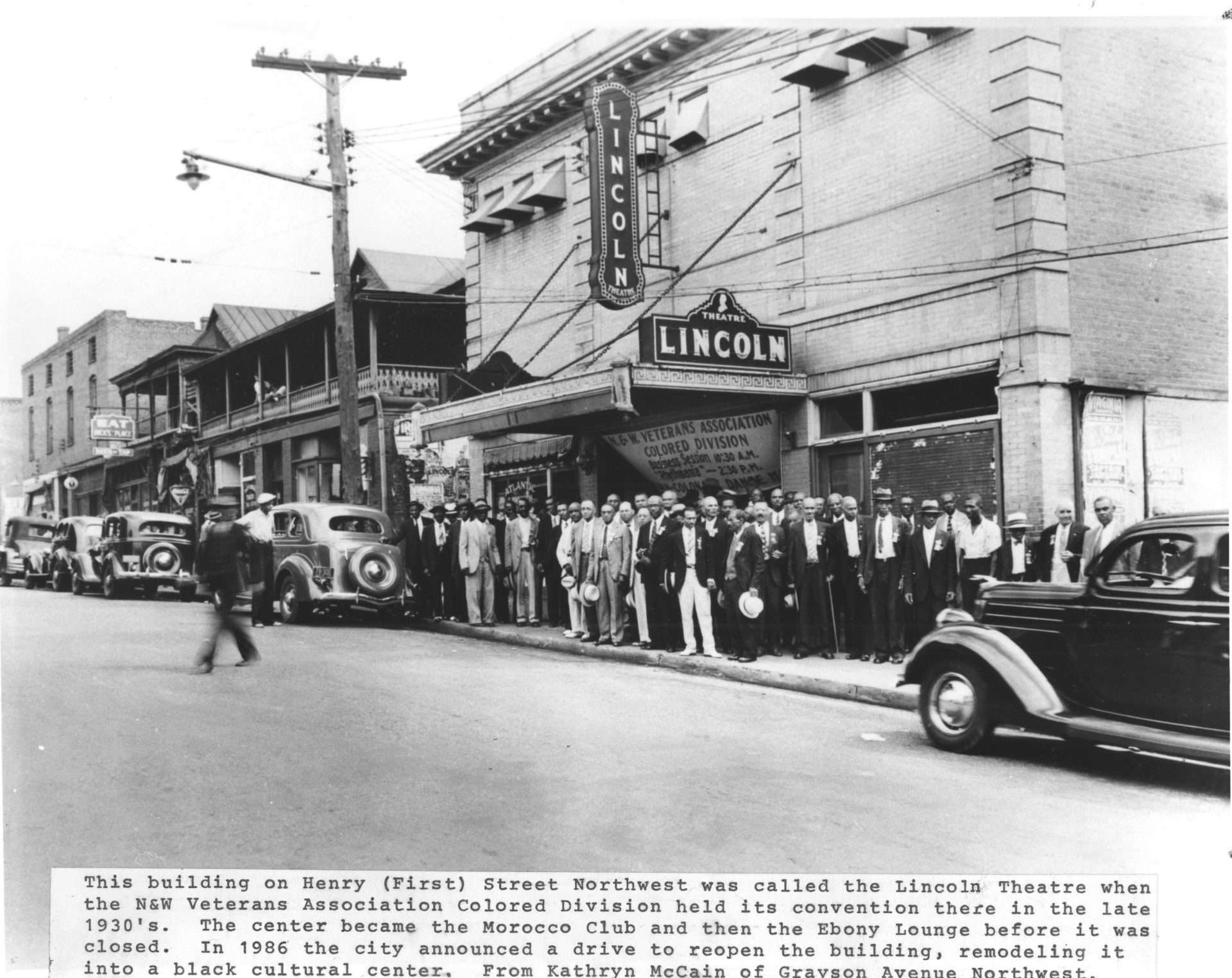

The Ebony Club is long gone, but the building, which was built as a movie theater called The Strand in 1923, still stands as part of the Claude Moore Education Complex owned and managed by the Roanoke Higher Education Center. The old theater houses Virginia Western Community College’s Al Pollard Culinary Arts program, and the interior remains intact and serves as meeting and classroom space.

The theater swells with history. Before it was a nightclub, The Strand showed movies for mostly Black audiences and was home to the film company of Oscar Micheaux, a pioneering Black filmmaker of the 1920s. The Strand — and its following iterations the Lincoln, Club Morocco and the Ebony Club — was once part of the heartbeat of Black commerce and entertainment on Henry Street, a business district that served Black Roanokers during the days of Jim Crow and segregation.

The street, which is now a Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places, was decimated following the 1960s as shoppers and residents left the area, sometimes forcibly. Desegregation made an impact, as the integration of stores and restaurants across the city provided Black Roanokers opportunities to shop and dine on the other side of the Norfolk & Western railroad tracks where they previously had been unwelcome.

But perhaps the biggest blow to Henry Street was the city’s policy of “urban renewal” in the 1950s and ’60s which leveled much of the Gainsboro sections of Northeast and Northwest Roanoke. Under what was considered a progressive plan of “slum clearance,” entire mostly-Black neighborhoods were scraped off the map, the residents uprooted, forced to sell their homes for demolition and then move to other parts of the city. Henry Street businesses were decimated by the loss of clientele in the wake of urban renewal.

On Saturday, Gainsboro advocates will celebrate the old Strand, the Ebony Club and other Henry Street entertainment landmarks with music, stories and food. Billed as the Strand Theatre Revival, the free event aims to raise awareness of Gainsboro history and the few remaining buildings along Henry Street.

Many of the most famous Black musical performers from the 1940s until the 1960s played at venues on Henry Street — Duke Ellington, James Brown and Otis Redding among them. Many of the famous performers stayed at the historic Hotel Dumas, a lodging destination that served Black travelers which still stands. But it was the local bands that kept the nightclubs buzzing with music. Musicians who remember those days recall the nightlife as reminiscent of the blues scene on Beale Street in Memphis.

“We were all well-known around the circuit,” Walker said of the bands that played around the region in the 1960s. “But we all ended up back on Henry Street.”

The dressing room, a stage - and Marvin Gaye

Henry Street pulsed with music and other entertainment into the 1960s. In addition to soul singers Brown and Redding, Jackie Wilson, Gladys Knight and the Pips, Fats Domino, Chuck Berry and many others performed at the Star City Auditorium at the corner of Henry Street and Wells Avenue. Other Black performers played at the American Legion Auditorium, which stood next to Hotel Roanoke, or at Victory Stadium.

Henry Street clubs such as the Amber Room, the 308 Club and Eric’s Lounge played host to local and traveling musicians, most of them playing jazz or rhythm and blues. In the middle of it all was the old Strand Theatre, later called Club Morocco and finally the Ebony Club.

Elmer Coles, 77, was an underaged teenage trumpet prodigy when he played the Ebony Club with the Chevies and the Premiers, one of Roanoke’s great R&B ensembles for more than a generation. Coles didn’t recall a ton of details about the Ebony Club — he was 14 years old when he played there — but he remembered the venue as a lively place where people danced in front of the stage or listened to music over drinks at their tables or at the bar.

“It had a long bar with a really nice mirror behind it,” Coles said. “It had a tiny stage with dressing rooms on the sides. People were mostly standing or dancing and having a good time. It was a party. Organized chaos.”

Walker remembered that the dressing rooms were unusual for a Roanoke nightclub.

“You could come right out of the dressing room onto the stage,” recalled Walker. He added that he always preferred the name Club Morocco to the Ebony Club.

Allan Walker, 77, a saxophone player who isn’t related to Woodrow Walker, said that, like Coles, he sat in with the Chevies and Premiers as a teenager at the Ebony Club. One highlight happened in 1964 when the band opened for Marvin Gaye at the Star City Auditorium. Walker said that as he watched Gaye perform set with a small backing band, the young saxophonist stood off to the side of the stage and began playing along with the songs. He said Gaye didn’t disapprove.

“I like to say that I played the Star City Auditorium with Marvin Gaye,” he said.

In a Roanoke Times news story that chronicled a 2001 reunion of local jazz and R&B players, the late Bob Macklin recalled taking his cornet into Henry Street’s jazz clubs in the evening and playing with a variety of combos until the sun came up. Some of the musicians who gathered at the reunion, all of them graduates of Lucy Addison High School in the days of segregation, told the newspaper that a musician could disappear into a Henry Street club on a Friday night and not emerge until Monday morning, so lively was the music scene.

Henry Street wasn’t the only corridor in town bursting with music. Black musicians were welcome at Papa Joe’s, a bar that often notoriously doubled as an exotic dance club just east of downtown. White players joined mostly Black ensembles in Henry Street clubs.

Allan Walker said that even the Chevies and Premiers’ afternoon practice sessions at the Ebony Club were popular with white musicians.

“White guys would come to the Ebony Club at 1 in the day to hear us play,” said Walker, who lived in Northern Virginia for 40 years and had a long career playing with international touring acts before returning to Roanoke recently. Later, Walker joined some of those white players in bands.

'Don't miss it'

The two-story Strand Theatre was always in the middle of the action.

The theater was built in 1923 by Albert F. Brooks and C. Tiffany Tolliver, two Black businessmen and developers, according to documents filed with the National Register of Historic Places. The movie palace featured a balcony and seated about 750 people who crammed the building to watch not only silent Hollywood blockbusters starring

Rudolph Valentino and Gloria Swanson, but also movies with Black actors during the Jim Crow era.

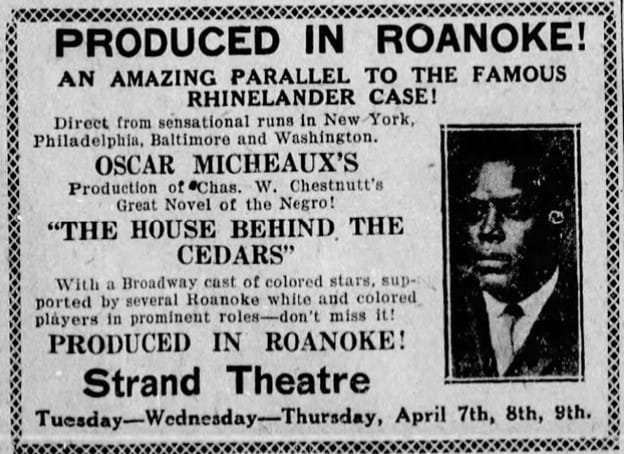

During its heyday as a movie theater, the Strand was famously the home base of Oscar Micheaux, one of the earliest and greatest Black film directors in America in the early 20th century.

Micheaux was born in Illinois in 1884 and worked for railroads and farmed before trying his hand as an author. In 1919, he was approached about turning his novel “The Homesteader” into a film, which launched him into the movie business.

He established the Micheaux Film Corporation and settled in Roanoke for reasons that aren’t exactly known. Some film historians believe his former railroad connections brought him to the city in search of movie-making capital, which he found in the heart of Roanoke’s Black entertainment and commercial heart of Henry Street, the home base for his company in the mid-1920s. He specialized in “race movies,” silent films that played to Black audiences in segregated theaters like The Strand.

He made several movies in Roanoke, featuring well-known Black stars as well as local actors, both Black and white. His film “The House Behind the Cedars,” based on a novel by the famous early 20th -century African-American writer Charles Chesnutt, included scenes shot on the 400 block of Gilmer Avenue in Northwest Roanoke. Like most of Micheaux’s films, no copy remains, but it is believed that one of the houses used for the movie was the boyhood home of Oliver Hill, a famous civil rights attorney from Roanoke who would participate in the Brown V. Board of Education case that would bring about the end of segregation.

Micheaux advertised his films widely, including in the pages of white-owned newspapers such as The Roanoke Times and the evening World-News. A 1925 advertisement in the World-News proclaimed that “The House Behind the Cedars” then showing at The Strand was “Produced in Roanoke!” The ad boasted that the film included “a Broadway cast of colored stars, supported by several Roanoke white and colored players in prominent roles — don’t miss it!”

Micheaux had to recut his film because Virginia censors banned the movie for its depiction of an interracial couple. Still, Micheaux made more than 40 films, six to eight of them shot in Roanoke, primarily in the Gainsboro neighborhood. A 1922 news article in the World-News reported that Micheaux had completed filming “The Virgin of Seminole,” probably his first picture made in the city, at various locations “in and around Roanoke.” The article stated that “Director Micheaux reports that he has filmed some of the most picturesque exteriors ever embodied in a picture in the Mountains and valleys that surround the city.”

No copies of any of Micheaux’s Roanoke-made movies survive. According to a historic marker outside the old Strand Theatre, Micheaux’s film company operated in the city until 1925.

Bringing back energy and memories

Nadirah Wright’s family wouldn’t let her set foot in Club Morocco or the Ebony Club when she was a girl growing up in the Hurt Park neighborhood in the 1960s.

“They felt like I wasn’t mature enough,” said Wright, who admitted to sneaking peeks inside the Star City Auditorium when the big-name acts rolled into town.

Wright, 73, later sang with the girl group the Soulettes in the 1960s and ’70s, and she eventually performed inside the Ebony Club when neighborhood advocates hoped to revive the old theater in the 1980s and ’90s. After moving back to Roanoke following a career with the General Accounting Office in Washington, D.C., Wright sang in the musical “Henry Street!” written by Roanoker Greta Evans.

Wright will be one of the featured performers during Saturday’s event. She will be accompanied by keyboardist William Penn as part of a bill that includes the OG’s and singer Sissy Jackson.

The event is free and will include food, but, unlike the old days when customers could bring their own bottles, alcohol won’t be allowed. Attendees are encouraged to bring photographs of Henry Street and the Gainsboro neighborhood. The show is supported by the Arts Connect Neighbors program funded by the city and by the National Endowment for the Arts.

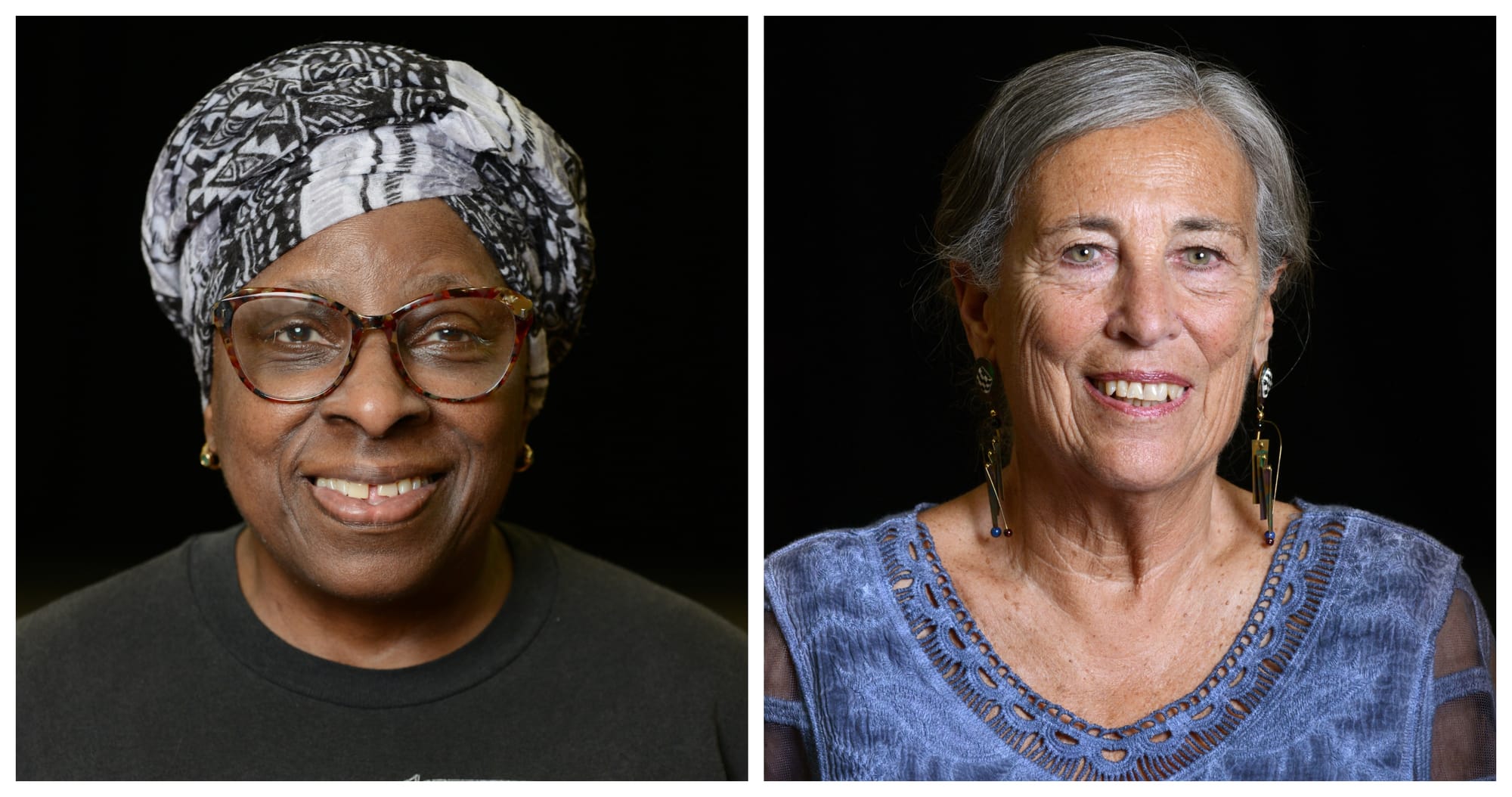

“We want to bring back the energy and the memories of what once was there,” said Wendi Schultz, one of the event’s founders.

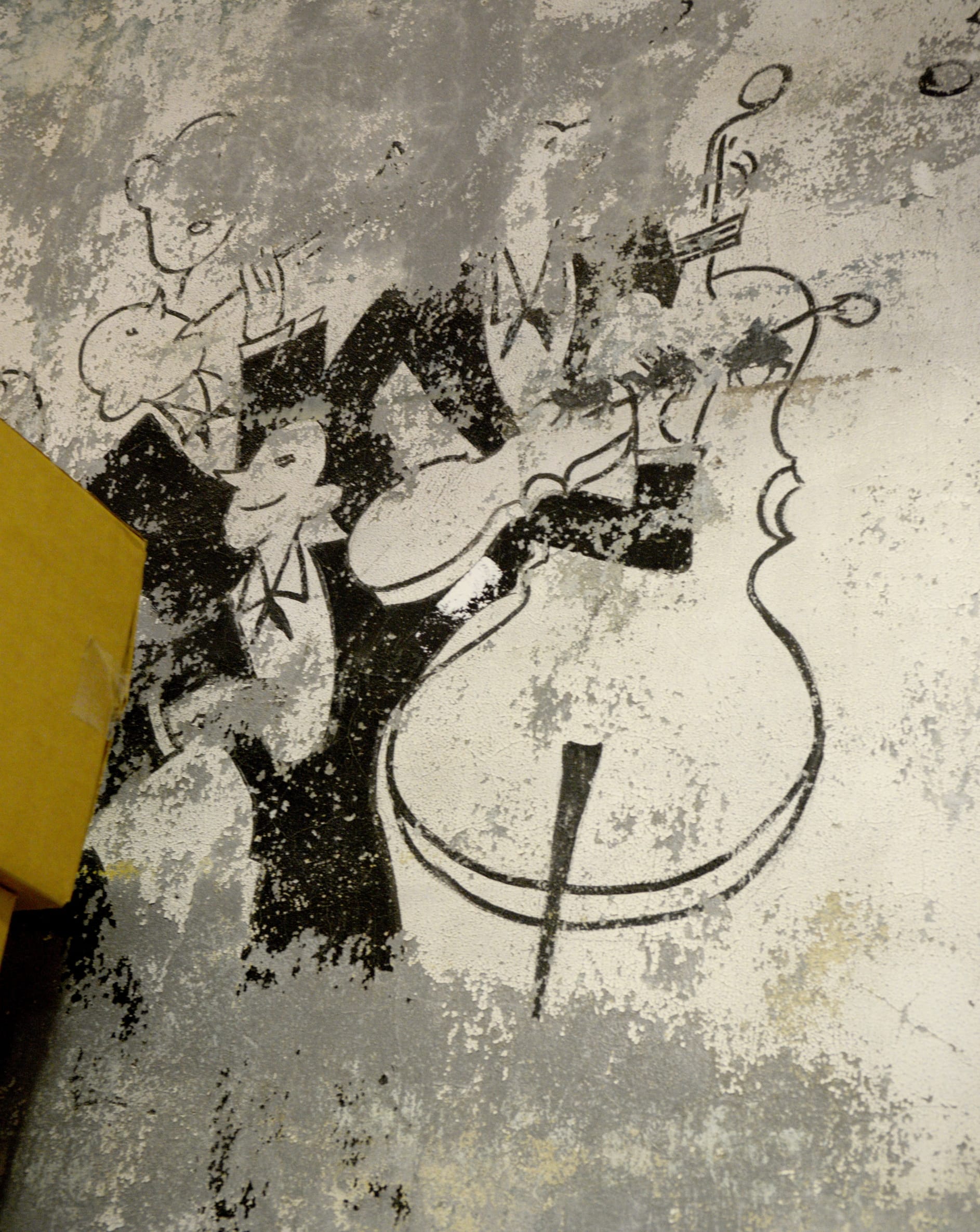

Schultz pointed out a black-and-white, cartoon-like mural painted on a rear wall behind the theater’s stage that depicts a group of musicians. She doesn’t know the history of the mural or how long it has been on the wall, but she hopes someone who comes to the Saturday show will know the story.

The event is nearly two years in the making, following an idea hatched by Schultz and Charlie Finesilver, who moved to Roanoke a couple of years ago from South Carolina.

One day while taking a stroll in the downtown of his newly adopted city, Finesilver walked across the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Bridge toward what remains of Henry Street. He noticed the few buildings occupied by the culinary school and the Hotel Dumas across the street.

“I wondered, ‘what am I looking at here?’” Finesilver said. “It was quiet and deserted, but everything looked amazing.”

He eventually met Schultz, who spent a long career producing and promoting large- scale regional events, first as the executive director of Festival in the Park and later as the tourism and events coordinator for Roanoke County. The two worked closely with Constance Crutchfield, president of the Gainsboro Neighborhood Organization, Megan Mizak, head librarian at the Gainsboro Branch Library, and with administrators of the Higher Education Center to plan the concert.

The center allows the community to use the old theater space for free for educational events. Yvonne Campbell, Dean of Virginia Western Community College’s School of Business, Technology, and Trades, which oversees the culinary school, said that the concert qualified as an educational service.

“It’s a celebration of the jazz clubs and the culture of the neighborhood,” said Campbell, who added that the Gainsboro Neighborhood Organization must also approve any event held in the space.

“There is a lot of historical significance in that space. It’s a chance to go back in time and remember what the culture was like.”

The organizers hope they can hold future events that pay tribute to Gainsboro's history. “Maybe we can do more occasional concerts,” Finesilver said. “We'd love to work with the Higher Ed Center to create more of these moments. The people of the community have really gotten behind this. They're pitching in from all directions.”