The Rise and Fall of Robert Jeffrey Jr.

This is an account of Jeffrey’s ascent to power in Roanoke, and his swift downfall across two criminal trials last week.

Robert Jeffrey Jr. was on top of the world.

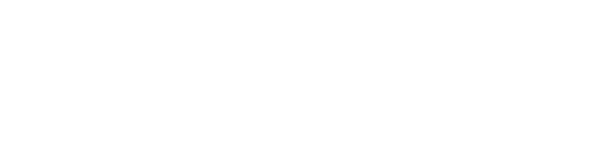

It was 11:40 p.m. on November 3, 2020, election night, and he had just been swept into power with fellow Democrats Mayor Sherman Lea and Vice Mayor Trish White-Boyd. His win as the second-highest vote getter countered a narrow loss when he ran for City Council two years earlier.

On this fall night, the victorious gathered in a south Roanoke church along with other dignitaries. A shaky Facebook Live video captured the jubilation.

“I just want to say congratulations,” said Anita Price, an outgoing member of City Council who didn’t run for reelection. “We all know how hard this campaign has been but we have found that if you just keep the faith … keep on pushing, look what happens in the end. Congratulations to you all.”

“This is my brother,” Price said, turning to face the camera and pointing to Lea.

“Trish, that’s my sister.” Price pointed to White-Boyd.

“Robert.”

Price paused. The camera panned to Jeffrey as the sound of Price apparently clasping her hands echoed.

“So happy for you,” she said.

The Southern praise may have betrayed a subtle sign: Even at Jeffrey’s peak, some Roanoke leaders maintained a wary distance from — or, at least, an unfamiliarity with — the political newcomer. (Price did not respond to messages for this story.) During his 2018 run for Council, details emerged that raised questions about Jeffrey, the founder and chief executive officer of Jeffrey Media, which published a monthly magazine celebrating people of color in Southwest Virginia.

Six former contributors to ColorsVA Magazine had published a letter in the newspaper accusing Jeffrey of not paying them for work. Three filed civil lawsuits. (All were eventually dismissed). Jeffrey had filed for bankruptcy in 2010. And it also emerged, a month before the May 2018 election, that in 2017 Jeffrey failed to pay $3,600 in child support payments to an ex-wife.

It was not the first time people had accused Jeffrey of ripping them off.

It would not be the last.

The Rise

In 2013, Jeffrey, now 52, returned to his Roanoke hometown to begin a new life. After 20 years in Seattle, he left after the Great Recession fueled the collapse of his business, a personal bankruptcy and a messy divorce.

This account of Jeffrey’s ascent to power in Roanoke, and his swift downfall across two criminal trials last week, is based on records, court proceedings, media reports and interviews with numerous people who know Jeffrey.

Robert Lee Jeffrey Jr. came of age in the Roanoke of the 1970s. His mother, Evangeline, is a longtime community and civil rights activist. She integrated her Bedford County high school and as a college student joined sit-ins at segregated Lynchburg restaurants. Throughout the 1980s, Evangeline Jeffrey served as president of the Roanoke branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Jeffrey’s father, Robert Sr., ministered at Pilgrim Baptist Church. Robert Sr. moved to Seattle in 1986 after Jeffrey’s parents divorced.

One Sunday, when Robert Jr. was young, the family came home from church to find their house on Wilmont Avenue had been vandalized. The N-word was painted on a wall, Evangeline’s jewelry had been stuffed down a toilet and NAACP records were destroyed.

At Roanoke City Public Schools, Jeffrey took part in a program where he shadowed lawyers in the city prosecutor’s office — then, as now, under the leadership of Commonwealth’s Attorney Don Caldwell. Around this time, Jeffrey told his mother he wanted to become a lawyer. After graduating from William Fleming High School in 1987, Jeffrey went to Hampton University, a historically Black college, where he earned a degree in business.

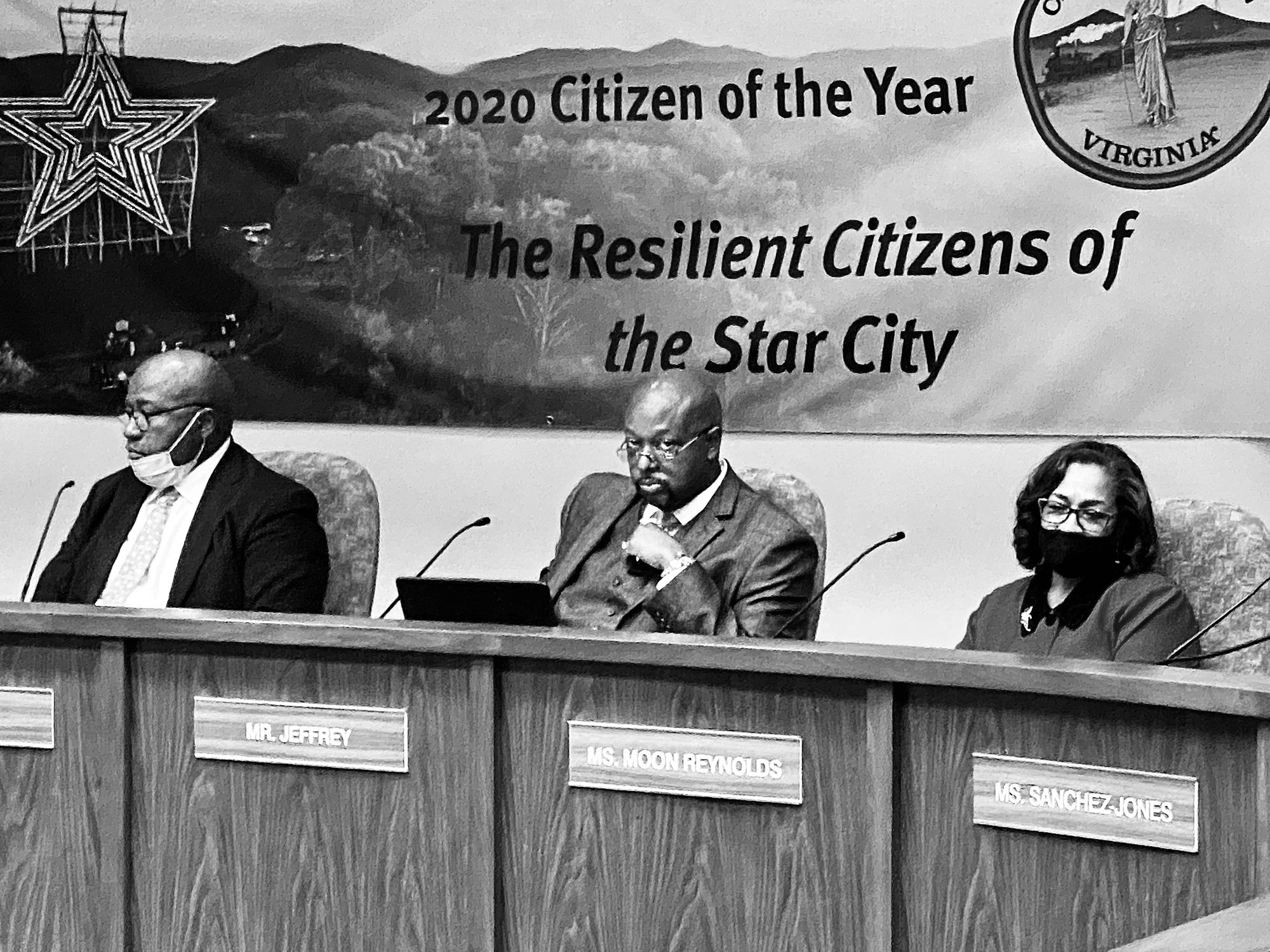

Shortly after college, Jeffrey moved to Seattle. He held various positions at The Seattle Times, where as an account executive he claimed to have overseen more than $11 million in annual sales. A decade later, Jeffrey and his then-wife founded ColorsNW, a monthly magazine focused on telling the stories of people of color in the Pacific Northwest. The publication won numerous journalism awards before the economy cratered, shuttering the business.

In 2010, Jeffrey and his wife divorced and he filed for bankruptcy, citing $2.2 million in debts. Despite the bankruptcy, creditors would continue to pursue Jeffrey in court — including at least one former employee of ColorsNW — claiming he owed them money. In the years to come, one line from his ex-wife in divorce papers would prove prescient, taking into account Jeffrey’s penchant for blurring his business and personal finances: “He uses Colors NW, Inc as his personal bank account and I have no way of knowing what his true income is.”

***

When Jeffrey moved back to Roanoke, he embarked on recreating Colors magazine for a Southwest Virginia audience. In May 2015, he incorporated Jeffrey Media in Virginia and began publishing ColorsVA Magazine that summer.

The publication was largely well received, with several community leaders saying its focus on diversity was needed in a city with a complicated history of segregation and racism.

“Roanoke is a very diverse community,” Kiesha Preston, a local activist who wrote a few stories for ColorsVA Magazine in 2019, said in an interview last week. “It kind of sheds light on, you know, the accomplishments and achievements and things that are going on in lots of different communities. And I feel like Roanoke is definitely lacking that, so I definitely feel like the magazine itself is very needed here.”

In May 2016, Jeffrey became one of 11 people to receive a Citizen of the Year award from the Roanoke branch of the NAACP. President Brenda Hale heralded the winners as making a positive difference in the community. (Hale declined to comment for this story.)

In October 2016, Jeffrey married Tina Williams. He had loved her since he was a senior at William Fleming, Jeffrey has said. It was Jeffrey’s fourth marriage, and her first. Robert Jeffrey Sr. officiated the wedding in Roanoke.

A month later, Donald Trump won the presidency, and in August 2017, white supremacists descended on Charlottesville. Jeffrey would cite both events as fueling his political ambitions.

In November 2017, Jeffrey became the first candidate to announce his bid for City Council, seeking a Democratic nomination. At the time, elections were held in May 2018. During the campaign, Jeffrey talked about the need to help small businesses, address the city’s problem with gun violence and improve community health.

In a race for three City Council seats, Jeffrey came fourth, missing out by 325 votes.

During the campaign, some of Jeffrey’s financial troubles came to light. Some went unreported, while other issues were yet to come. Printers of ColorsVa Magazine took Jeffrey’s company to court, saying they had never been paid. In April 2017, Associated Publishers Distribution, a Roanoke-based printing company, settled out of court. Two years later, Progress Printing Company, a Lynchburg-based business, claimed Jeffrey owed more than $10,000. In July 2019, a Roanoke court ordered Jeffrey to pay the full amount.

“He had some issues at that time, probably dealing with finances and businesses,” Mayor Sherman Lea said in an interview this week about Jeffrey’s 2018 campaign. “At that time [I told him], get your stuff straight, get your house in order. And then if you still want to do it, try it again. And that’s why I said, when I talked about disappointment, I thought he had gotten it behind and then moved forward.”

“I thought he was a young man that was on the move in the Democratic Party,” Lea added.

After his failed Council bid, Jeffrey bolstered his community service ties, joining the boards of Goodwill Industries of the Valley and the United Way of Roanoke Valley in 2019.

“Because of his extensive multi-media background and experience as a small business owner, he was recruited to join the marketing committee within the Board,” Connie Stevens, a spokeswoman for United Way, said in an email.

Jeffrey also became vice chair of the Roanoke City Democratic Committee.

When the coronavirus pandemic upended daily life, city Democrats decided to pick their candidates through an online vote by the committee’s 77 members. In that May 2020 primary, Jeffrey came in third with 47 votes, ensuring his name would appear on the general election ballot. That positioned him well for that November.

While one of the party’s candidates would lose to an independent, Roanoke voters have often picked Democratic candidates in local elections. Jeffrey came in second place, with about 13,200 votes out of nearly 93,200 ballots cast.

Just after the election, Jeffrey called his win “surreal,” and said he was ready to get down to work. He was sworn into office the following January.

His political honeymoon would not last long.

The Fall

On the chilly morning of Monday, March 14, 2022, Jeffrey arrived at the Oliver W. Hill Justice Center, Roanoke’s downtown courthouse, with an air of confidence. Beneath a camel-colored topcoat, he wore a dark suit, bright red tie, and French cuff shirt.

It was the first day of two back-to-back jury trials.

The previous summer, Roanoke prosecutors made an explosive announcement: A grand jury had indicted Jeffrey on July 6 on two felony charges of embezzlement. The Commonwealth’s Attorney’s office said the sitting city councilman had stolen money from the nonprofit Northwest Neighborhood Environmental Organization (NNEO), for which he had managed property.

In early October 2021, a grand jury approved two new felony counts: obtaining money by false pretense. Prosecutors accused Jeffrey of defrauding Roanoke’s Economic Development Authority out of federal pandemic relief funds to use for his magazine and property management businesses.

With new charges came new calls for Jeffrey to step down from City Council. After the court pushed Jeffrey’s initial October trial date back to March, his colleagues on Council passed a resolution encouraging Jeffrey to take a leave of absence until the case concluded.

“I understand the reason why my colleagues would have to do this, to get to this measure, but I also understand some of these reasons are political in nature,” Jeffrey said at a Council meeting then. “My intent is to stay in office. … I will do that until my court date, to where I will be vindicated from these charges.”

Prosecutors would first try the case accusing Jeffrey of defrauding the city out of pandemic relief funds. They would then turn their attention to the embezzlement case in a second trial.

During the first jury selection last week in Roanoke City Circuit Court, Judge David B. Carson asked whether anyone had heard of Jeffrey or the case in the media. No jurors raised their hands.

“This is not a complicated case,” Sheri Mason, an assistant Commonwealth’s Attorney, told the jury.

During the prosecution’s opening statement, Mason laid out the evidence: In the summer of 2020, the city earmarked $1 million in small business grants funded through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. Many small businesses were struggling to pay employees as the pandemic wreaked havoc on the economy.

Among the applicants were two of Jeffrey’s businesses: Jeffrey Media and RLJ Property Management. The city’s Economic Development Authority, which oversaw the program, decided to limit grants to businesses in operation before March 2020. Another criterion: Businesses with three or fewer full-time employees were eligible for up to $1,250, while those with four to 20 full-time employees could get up to $7,500. The application defined full-time employees as those working at least 30 hours per week or 130 hours per month.

That December, Jeffrey’s businesses received $15,000 after his applications stated Jeffrey Media employed five full-time staff and RLJ Property Management had six full-time workers.

Karen Jones, the editor of ColorsVA Magazine until last October, testified that she had also worked as a bookkeeper for RLJ Property Management, which wasn’t established until the summer of 2020. She said she had never worked more than 30 hours in a week at either business and wasn’t aware of anyone besides Jeffrey who did.

In the beginning stages of the trial, Jeffrey’s defense attorney, Jonathan Kurtin, questioned whether Jeffrey’s workers — who were either contractors or freelance journalists — couldn’t also be considered full-time employees. But as the trial proceeded, a different tactic emerged: That fact didn’t matter, because Jeffrey wasn’t the one who applied for the grants.

“You are asking the jury to accept what you say as the truth?” Kurtin asked Jones.

“Yes,” Jones said.

“Do you think the jury should know about your own past?”

“Absolutely. … I do have two felony embezzlement convictions.” Jones said. A murmur spread through the courtroom.

“You say you stole from two of your former employers?”

“I did.”

“I have no further questions.”

Jackie Johnson, who also worked for both of Jeffrey’s businesses, testified that she never worked more than 30 hours in a week, except once, according to a time sheet for the property management company, in November 2020: She said she was paid to help on Jeffrey’s campaign for City Council.

Marc Nelson, the city’s economic development director, said staff were working quickly to get CARES Act money out the door and assumed applicants were being honest. One staff member testified he had talked by phone to a man who identified himself as Jeffrey to confirm the numbers on his applications, which listed Jeffrey’s name as an electronic signature.

“If someone at Jeffrey Media or RLJ Property Management, if someone was a thief — and we know that because they've already been convicted a couple of times of embezzlement — they could have done that electronic signature?” Kurtin asked Nelson.

“They could have,” he said.

“We live in a day and age, unfortunately, of identity theft, and that’s really what this case is about,” Kurtin said in closing, telling jurors a conviction would end Jeffrey’s life. “His, literally, very life is in your hands. … He’ll be a convicted felon. You can sentence him to the penitentiary.”

In closing, Mason read from a list of bank expenditures after the $15,000 in pandemic relief money was deposited: $683 to an investment fund in Jeffrey’s name, $295 to Frankie Rowland’s Steakhouse, $1,060 for child support payments, $150 to Victoria’s Secret.

“Guess what wasn't on there?” Mason told the jurors. “You take a look at it.” Besides her regular pay and a $100 Christmas bonus, “Not a single check was written to Karen Jones.”

After 25 minutes, whispers spread in the court lobby that the jury had reached a verdict.

Everyone filed into the courtroom. Eight white people and four Black people appeared to make up the jury.

Jeffrey stood and clasped his hands.

As the jurors faced the judge, Carson read their verdict on the Jeffrey Media charge: Guilty.

“Oh Jesus,” Evangeline Jeffrey said.

Carson read the verdict on the RLJ Property Management charge: Guilty.

Jeffrey’s wife, Tina, looked skyward and blinked.

Behind a blue medical mask, Jeffrey showed no outward sign of emotion. The jury filed out.

Turning his attention to Jeffrey, Carson said: “As you now stand stripped of the presumption of innocence that you would normally be entitled to and now stand as a convicted felon, I remand you to custody.”

Jeffrey dropped his car keys on the table. Sheriff’s deputies escorted him out a back door to a hallway that connects to the city jail.

***

On Wednesday morning, prosecutors offered Jeffrey a deal: He would plead guilty or “no contest” to one embezzlement charge and the Commonwealth would drop the second.

Jeffrey refused. The second trial would proceed.

But the night in jail had not treated Jeffrey well. He could not get his medication. Before the trial began, Tina Jeffrey appeared to ask Kurtin how Jeffrey was doing.

“He’s very depressed,” Kurtin replied. “He’s trying very hard to hide it, but he’s very depressed.”

Kurtin said Jeffrey may need to be in a wheelchair but that he didn't want to be seen in that state. Jeffrey had been undergoing dialysis for kidney issues, and his mother said in an interview that he was suffering from gout.

During the selection of a new jury, Jeffrey walked stiffly to the defense table. He wore a gray checkered suit and brown-gray tie, the same as the day before. By the time the trial’s opening statements began in the afternoon, a sheriff’s deputy rolled Jeffrey into the courtroom in a wheelchair.

“Has anyone ever heard the expression ‘don’t bite the hand that feeds you’?” Mason told the jury, rattling off definitions. “Those synonyms would be very applicable to what Mr. Jeffrey did to the NNEO.”

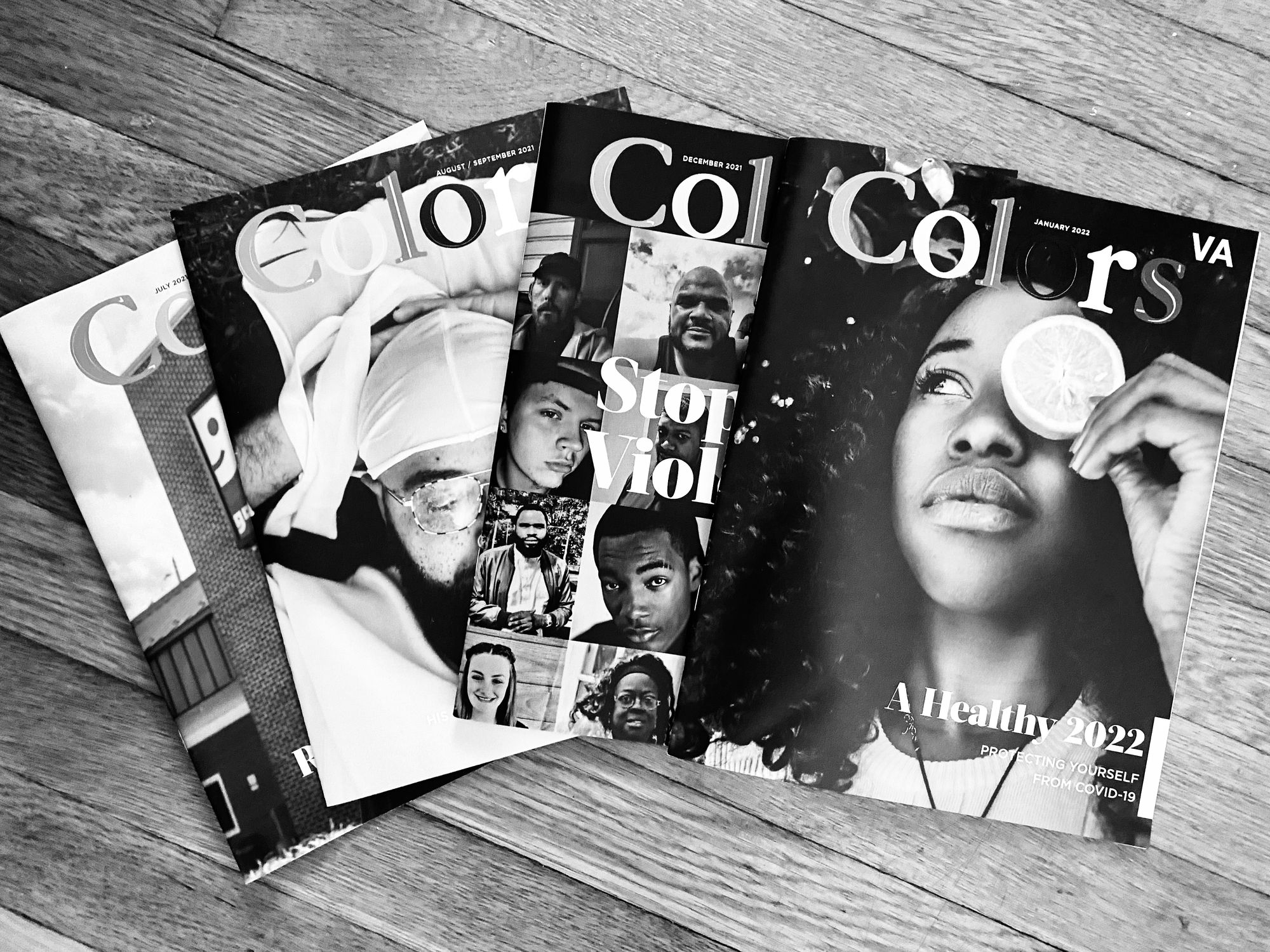

The neighborhood organization operates two apartment complexes for elderly people on low incomes: McCray Court and Gilmer Housing. In 2019, Evangeline Jeffrey, who served as the vice president of NNEO, suggested Robert could assist the group, and he proceeded to help make repairs to the Gilmer apartments.

The NNEO board was impressed, so in July 2020 they contracted with Jeffrey’s new company to manage McCray and Gilmer. His firm would be paid $8,100 a month to oversee the apartments, including hiring workers for maintenance issues. Jeffrey would also have access to NNEO bank accounts.

By the fall of 2020, the nonprofit board started to become suspicious of some expenses.

André Peery, a board member, testified that he went through bank records and compiled a list of questionable transactions. They included: more than $10,000 in construction on Jeffrey’s childhood Wilmont Avenue home, owned by his mother; more than $3,000 in appliances, including a stove, fridge, washer and dryer delivered to the home; and more than $3,500 spent on a bed and kitchen table delivered to the home.

In addition, Jeffrey spent NNEO money on lawn care services at his own home and on meals at expensive Roanoke restaurants.

“Mr. Jeffrey did all of those things,” Kurtin said. “The question is why did he do them?”

Kurtin told jurors that the expenses were authorized. He said Jeffrey was renovating the house on Wilmont Avenue for NNEO transitional housing. And food and drinks at the Hotel Roanoke, Frankie Rowland’s and Billy’s were part of fundraising efforts, Kurtin said.

“Have you ever heard of transitional housing?” Mason asked Peery.

“I’ve heard of it, but it’s not something that we were doing,” he said.

“Did anyone at the board meeting ever speak up and say that people needed to be wined and dined for fundraising efforts?” Mason asked him another time.

“No,” Peery said. “In fact, we weren’t doing fundraising.”

After Jeffrey didn’t provide the board with satisfactory answers about some of the expenses, NNEO filed a police report in May 2021. More than $100,000 was unaccounted for, Mason would later say.

“We kind of had to do something,” Peery testified. “We either did something or now we become liable for whatever went on. And we thought we better come clean with this. It wasn't pretty. It was not something we wanted to do. It was something we had to do.”

Jeffrey’s father, who had flown in from Seattle for his son’s embezzlement trial, grumbled to one of his son's friends during a break in the trial.

“That’s some petty shit,” he said about prosecutors mentioning expenses on hotels and meals.

For months, Jeffrey had expressed confidence he would be vindicated in court: He was innocent. If his father’s candid comments provided any clues, Jeffrey Jr. might have believed — might believe still — that he really was, that he had done nothing wrong.

“Everyone does that on expenditures,” Jeffrey Sr. said. “It’s called discretionary” spending.

“It’s not like he bought a jet or a fancy car,” Jeffrey’s father added.

The day ended in relentless minutiae and damning evidence: How a contractor did work on the Wilmont house, how he received McCray Court checks with “Gilmer” in the memo line; how police apprehended Jeffrey and found two versions of Peery’s list, with handwritten notes, different explanations for why Jeffrey had made certain expenditures.

On Thursday afternoon, before the trial resumed, Jeffrey agreed to a plea deal, the same that was offered Wednesday morning. Prosecutors would drop one charge, and he would plead “no contest” to a second and be found guilty.

“Did you decide, and was it on your own, to plead no contest to that charge here today?” Carson asked Jeffrey.

He sat slumped in a black suit in his wheelchair.

“Yes.”

“Are you doing that, sir, freely and voluntarily?”

Long pause. “Yes.”

Carson scheduled Jeffrey’s sentencing for June 7 and he was wheeled out. The three felony convictions each carry a maximum sentence of 20 years in prison.

Outside the courthouse, Tina Jeffrey yelled at a gathering of reporters.

“They had already convicted him in the media,” she said. “You convicted him without a jury or anything else. … They found him guilty before he ever had a chance to defend himself.”

She got into a car and sped west.

The End

The moment the judge approved Jeffrey’s plea agreement — a conviction that cannot be appealed — Jeffrey forfeited his seat on Roanoke City Council. Under state law, the city attorney determined, an elected official gives up their office upon a felony conviction and after appeals are exhausted.

It was the end of a saga that had cast a pall over city government for nearly nine months.

“I'm disappointed and sad for the citizens of Roanoke who have had to come along for this terrible ride,” Del. Sam Rasoul, a Democrat from Roanoke, said in an interview. “We should all do our part to ensure that we research candidates, vote for candidates and expect our elected officials to do right by them.”

Rev. Carroll Carter, president of NNEO, said the situation with Jeffrey took up so much of the nonprofit’s time, effort, paperwork and meetings.

“J-U-S-T-I-C-E,” Carter spelled out when asked for his reaction to the trial's outcome. “To have this concluded means that we can turn the page, and now we’re back on housing, taking care of this community, helping this community develop like it should develop.”

Lea, the mayor, said he feels bad about the victims — the city and NNEO — and disappointed in a man who became a friend.

“I was surprised by a lot of things that came forward, because he seemed to be a pretty astute businessperson, at least when we talk about business affairs here in the city,” he said.

Lea described Jeffrey as a critical thinker who came prepared to City Council meetings with good questions and ideas about infrastructure issues in Northwest Roanoke and dealing with poverty.

“Compared to me, he’s still a young man, and you can get your life straight, so I hope he learns from this episode,” Lea, 70, said. “My reading of Scripture says you got to forgive people, and I do that. So, we’ll go on.”

Black leaders in the community, including Lea, agreed that some of the intense media coverage of Jeffrey’s ordeal struck them as the product of a double standard.

In the January issue of ColorsVA Magazine, Jeffrey himself claimed that there are “prominent white people in the community who have done far worse,” than what he was accused of, and that “there has been little to no stories written about them.” He did not elaborate on those allegations.

“I talked to one wise and prominent black woman in our community, and she said, ‘Our black male leaders in Roanoke always have been targeted in some form or another in some character assassination or another,” Jeffrey wrote.

In an interview, Evangeline Jeffrey maintains her son is innocent and the victim of a conspiracy by NNEO. “I think Robert kind of captured it in his first statement to the press when he said, ‘It’s like crabs in a barrel,’” she said. “That’s a saying that a lot of African Americans use. … You know how crabs are, if one tries to get out of the barrel, the other ones pull them down.”

Preston, the local activist, said she does not see Jeffrey’s downfall as a case of “people trying to tear him down simply because he’s a Black man,” noting that Jeffrey pleaded no contest to one of the embezzlement charges. As for media coverage: “It's very real that these things are covered a little bit differently for people of color, but also it's very real that, you know, he's in a position that naturally draws this type of attention,” she said.

Preston, who ran as an independent in the 2020 City Council race, said her campaign touched on similar issues as Jeffrey’s, including equity and community engagement.

But she expressed disappointment with Jeffrey’s 15 months on Council, particularly his vote to ban camping on downtown sidewalks, which she views as criminalizing homelessness.

Councilman Bill Bestpitch was also unimpressed with Jeffrey’s time in city government.

“I just don't think he brought a lot to the table,” Bestpitch said.

Bestpitch recalled a publisher’s letter Jeffrey had written in an early issue of ColorsVA Magazine that rankled him. The letter claimed that recent changes to the city’s voting precinct boundaries meant some residents had to drive 20 minutes to a polling station, which isn’t true.

“He just made up all this stuff and put it in an article and published it in the magazine,” Bestpitch said. “So from that day on, I really kind of had to wonder how credible the guy is.”

Some months after the indictments against Jeffrey came out, Bestpitch and Jeffrey had a one-on-one. Jeffrey told Bestpitch he was innocent and would be acquitted. Bestpitch didn’t buy it.

“I told Robert this many months ago, one of the things I know about Don [Caldwell] is he does not like to lose,” Bestpitch said. “There have been plenty of situations where victims of crime and even the police department thought he should bring somebody into court and if he didn't think he had the evidence to convict somebody, he didn't try the case.”

At City Council’s regular meeting on Monday, the dais was one member short. Jeffrey’s nameplate had been removed. His picture still hung in the lobby. On a fairly routine vote that evening to allow a property owner to close an alleyway, the city clerk read the roll.

“Mr. Bestpitch?”

“Aye.”

“Mr. Cobb?”

“Aye.”

“Mr. Jeffrey? … I’m sorry. Ms. Moon Reynolds?”

“Aye.” ...