'We Got Soft on Crime': As Gun Violence Spikes, Roanoke Mayor Is Among Democrats Rethinking State Criminal Justice Reforms

Mayor Sherman Lea said Roanoke should consider using stop-and-frisk among other approaches to crack down on violent crime.

When Republicans took control of the Virginia House of Delegates last year, several Democrats worried the state would roll back criminal justice reforms enacted after the 2020 murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police.

But for some prominent Roanoke Democrats, reversing those reforms may be a welcome change.

“We got soft on crime over the last administration,” under Gov. Ralph Northam, Roanoke Mayor Sherman Lea, a fellow Democrat, told The Rambler after a city meeting this month. “We’ve got to get more punitive.”

In a subsequent hour-long interview last week, Lea said Roanoke should consider using stop-and-frisk, the controversial practice popularized in New York City in the 1990s and 2000s; called on the General Assembly to restore certain powers to local police; and expressed frustration with the approach taken by Police Chief Sam Roman to fight crime.

Lea’s tough-on-crime rhetoric comes as Roanoke has experienced an uptick in shootings in recent years. In the past few months, other Democrats on Roanoke City Council have indicated a willingness to reconsider certain criminal justice reforms in attempts to address violent crime.

During a recent City Council candidate forum, Councilwoman Vivian Sanchez-Jones received the night’s biggest applause line when she advocated for changes to how bail is administered.

“It doesn't matter how much you pay the police and how much you retain the police if the laws are not going to be on their side,” Sanchez-Jones said in response to a question about how to deal with gun violence. “They would arrest somebody, and by the end of the day, they're out on the street. So I think that the state level needs to be changed.”

Granting bond and stopping cars

In the wake of Floyd’s death, the Virginia General Assembly passed numerous changes to the criminal justice system. Among those: Banning the use of no-knock search warrants; prohibiting police chokeholds; creating teams to respond to mental health crises; and empowering citizen review panels to hold police accountable.

Most discussion in Roanoke revolves around two recent reforms. One restricts police from pulling drivers over for certain offenses, such as a broken taillight, tinted windows, a loud muffler or the smell of marijuana.

Another law gives judicial officers — such as a magistrate or judge — discretion in granting a defendant bail. Previously, a magistrate would have to order a person held in jail if they were charged with certain felonies.

The reforms aim to reduce the number of people held in jails and curb racial profiling.

Police Chief Sam Roman told City Council this month that the laws have tied his officers’ hands.

“Some of the limitations that we experience in law enforcement,” Roman said, “were all derived from the 2020 special session of our General Assembly.”

Before police are done with jail booking paperwork, “offenders are out of jail on a very insignificant bond, and in many ways that can create a narrative of no accountability,” Roman said at a June Council meeting. When a person is released from custody, he said, “and in many cases reoffend, that is very frustrating for law enforcement, not to mention the victims that are associated with those crimes.”

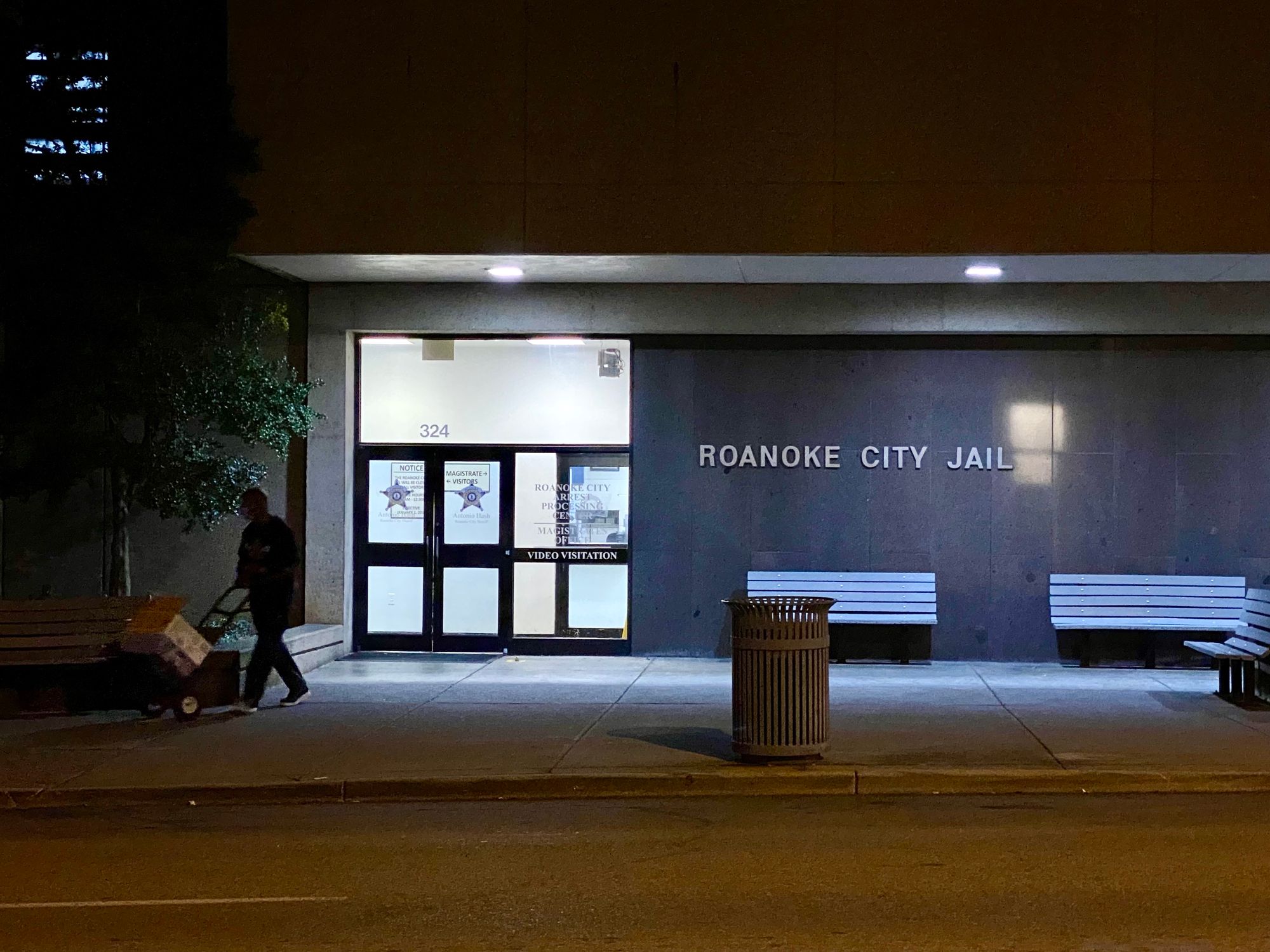

In a July press release, Roanoke police called out the magistrate’s office after a shooting injured a man in the Roundhill neighborhood. Police arrested Quintiy Steelman, 20, and charged him with malicious wounding and use of a firearm in commission of a felony.

“Within hours of his arrest,” police said, “Steelman was granted a bond by the Roanoke Magistrate's Office and released from the Roanoke City Jail.”

City leaders interviewed for this story said they had not heard of anyone recently being released from jail and committing another crime. The police department said it does not track data on the number of people released on bail.

Stephen Poff, chief magistrate, referred questions to the Supreme Court of Virginia’s Office of the Executive Secretary, which oversees magistrates. The office said Poff conducted a one-month review of recent bail decisions in response to City Council’s concerns. He met with Lea to discuss the issue.

“In all of the cases Mr. Poff reviewed, the magistrate had ordered the defendant held without bond,” Alisa Padden, director of legislative and public relations for the Office of the Executive Secretary, said in an email. “Since Mr. Poff’s review did not reveal any cause for concern with regard to Roanoke City magistrate bail decisions and no additional concerns or questions have been brought to our attention, we have no plans for a more in-depth review at this time.”

Councilman Joe Cobb, who chairs the city’s Gun Violence Prevention Commission, asked Roman at a meeting this month how Council could advocate for the police in its legislative priorities for the upcoming General Assembly.

“While we all appreciate and respect the importance of criminal justice reform, sometimes that can go to the extent that it prohibits you from doing the very thing that you need to do to resolve some of these crimes,” Cobb said.

Roman said he would begin with changes made during the 2020 General Assembly and “in cases where it’s appropriate, really roll back some of the preventive things that we are no longer able to do in primary.”

Cobb said Tuesday that criminal justice issues may be among the city’s legislative priorities, but that it was too soon to say what specific requests might be to state lawmakers.

“There were reform measures that I think were important, and sometimes you don't know what the longer term impacts are until you actually, you know, put some of these things in place and see how they're working,” Cobb said. “Have the reforms contributed to an increase in crime, or are there other factors that have contributed to that? And you might argue that it's a combination of both. But that's why I'm curious to see, you know, who in the state is tracking the effectiveness of these bills.”

Stopping, frisking and reevaluating

For Roanoke’s mayor, an uptick in gun violence has prompted him to reassess his support for certain criminal justice reforms.

“I am a Democrat. I supported the Democratic agenda, and I thought, at the time, it was the right thing to do, because the numbers and the data supported that,” Lea said when asked if he agreed or disagreed with the reforms when they were adopted. “But I’m concerned now there’s been a turn, a turn in violence for whatever reason. … And so it's going to cause us to change how we view some things.”

After meeting with Poff a couple weeks ago, Lea said he came away less concerned about the issue of bail. But he would like to see police given renewed authority to conduct certain traffic stops to check for guns and drugs. The mayor said he wants to see people arrested sooner, have trials sooner and face the maximum penalties when convicted of a gun crime.

Lea also advocated the use of stop-and-frisk, a practice that a federal judge in 2013 found was unconstitutional as carried out by New York City police.

“I think what New York did worked,” Lea said. “Back when [Rudy] Giuliani was the mayor and what he did in terms of stopping, frisking certain people to make sure you didn’t carry a weapon and those kinds of things. Some say it went to the extreme, but the numbers went down. Crime, gun violence, went down. And I think that’s something we have to consider. Not go to the extreme, but we’ve got to— we’re dealing with a different animal. Things have changed now.”

Asked if he was frustrated with Roman’s leadership, Lea paused for 10 seconds before saying: “There are times where we don’t necessarily agree.”

“I don’t agree on the approach that they take,” Lea said. “You know, I'm the kind of guy that if you’ve got this building over here and you know this is where the gangs hang out. … Well, I'm the [kind of] guy to get a van and go down there and look. And, you know, there's no law against being in a gang. But you got enough evidence, we got intelligence out here. Let's go and pick some people [up]. Send a message. Send a message. That's what these neighbors are calling for and telling us, that, ‘Hey, look, I know this is happening. You know that. We're afraid to go out there.’ That shouldn't be in the city.”

Since criminal justice reforms took place, Commonwealth’s Attorney Don Caldwell has been a vocal critic.

Caldwell said he doesn’t believe city officials bear any direct responsibility for the rate of crime in the city. But he said it would “be a big statement,” if Council’s legislative priorities would target reversing recent reforms, including on presumptions against bail and jury sentencing.

“I believe that the impetus is going to grow to return to some of the things we were doing,” Caldwell said. “And if our Democratic leadership in Richmond would be willing to reconsider some of what they’ve done, it would help.”

Democratic state lawmakers representing Roanoke rejected the idea that criminal justice reforms have had an influence on an increase in violent crime.

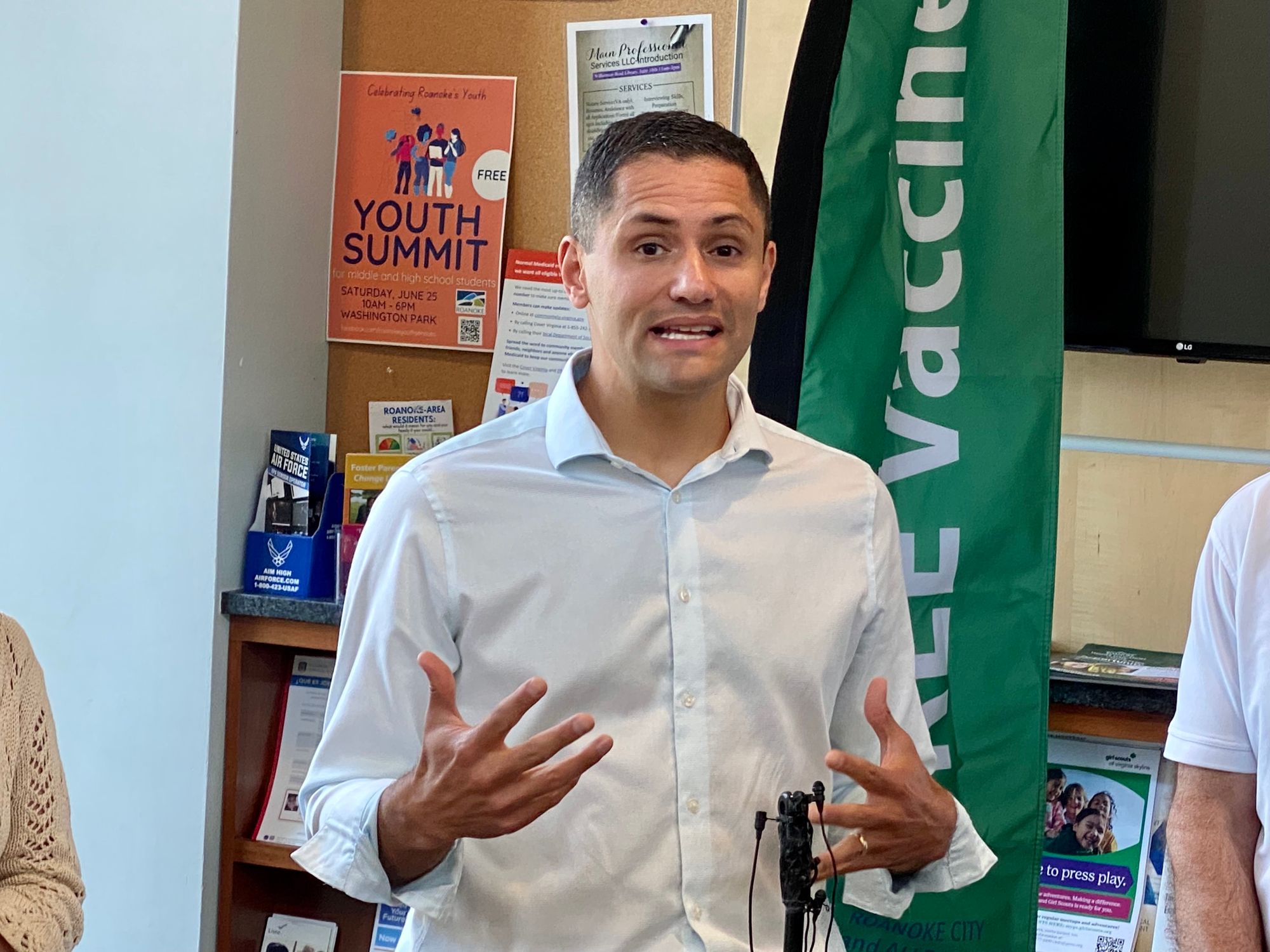

Del. Sam Rasoul said society needs a multi-pronged approach to fighting crime, particularly one that addresses poverty and homelessness. He said the state uses a significant amount of taxpayer money to keep people in jails and prisons.

“With regard to those who are incarcerated, Virginia is one of the toughest places on earth,” Rasoul said. “So those who begin with, ‘We need to incarcerate more people’ as the answer, we've been doing that for decades and it clearly doesn't work.”

Rasoul said he is “a big fan” of a lot of the criminal justice reforms enacted, but that he would be open to fine-tuning laws if it made common sense.

“Everything we do should be evidence-based,” Rasoul said. “And we should not be implementing policies and funding priorities that are knee-jerk reactions.”

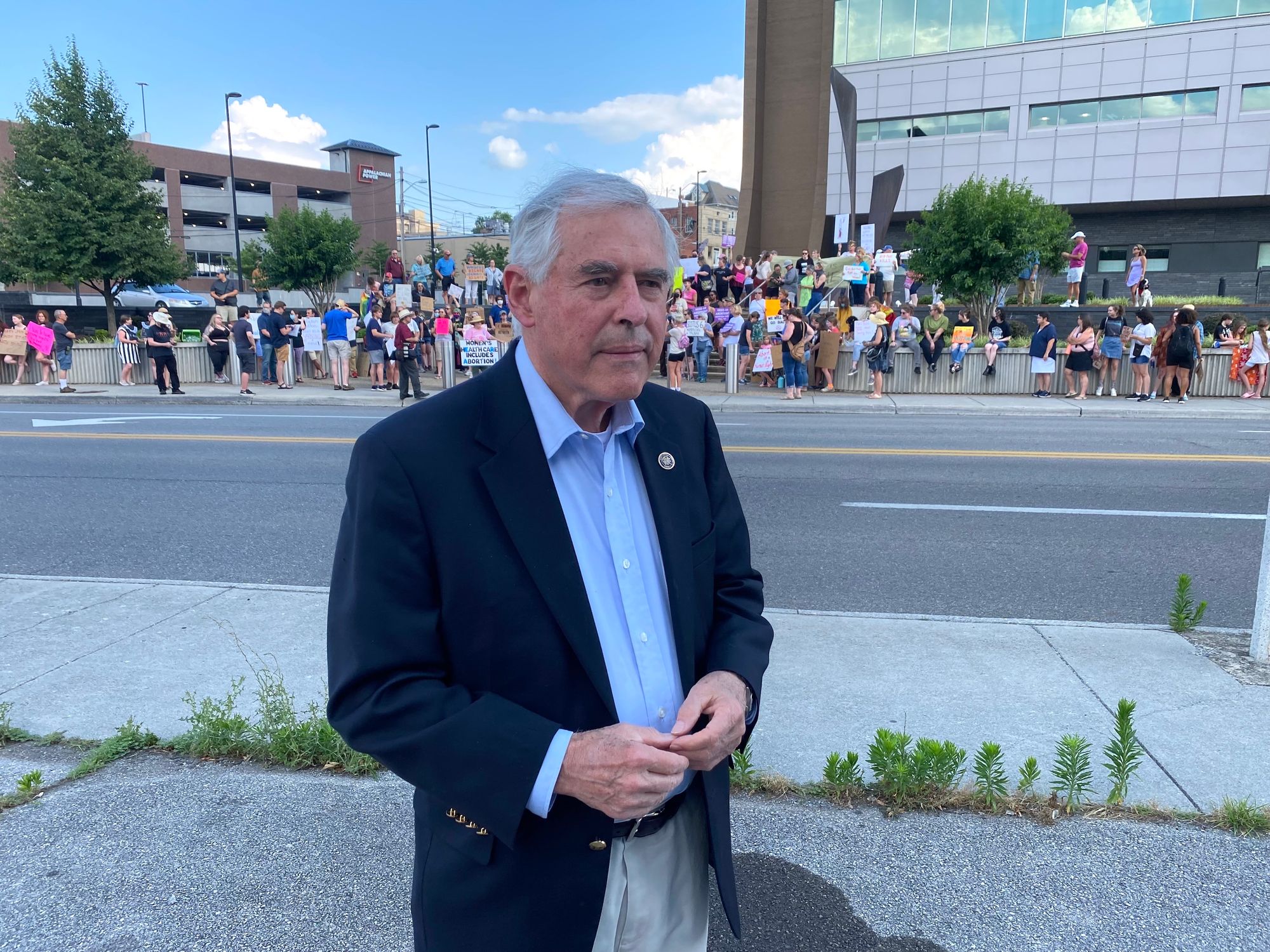

Sen. John Edwards chairs the Virginia State Crime Commission, which publishes reports on changes to the criminal justice system. He said he doesn’t think the General Assembly or a state agency will review how certain reforms are working.

“I think we did the right thing, and I stand by it,” Edwards said. “I’m proud of what we did, and I don’t know who’s complaining, but they don’t know what they’re talking about.”