Who Is Roanoke Police Chief Sam Roman? Sometimes Even He Doesn't Know For Sure.

Sam Roman's two years as top cop has faced a pandemic, gun violence, protests for racial justice and a severe officer shortage.

The senator seemed intrigued by Sam Roman’s introduction.

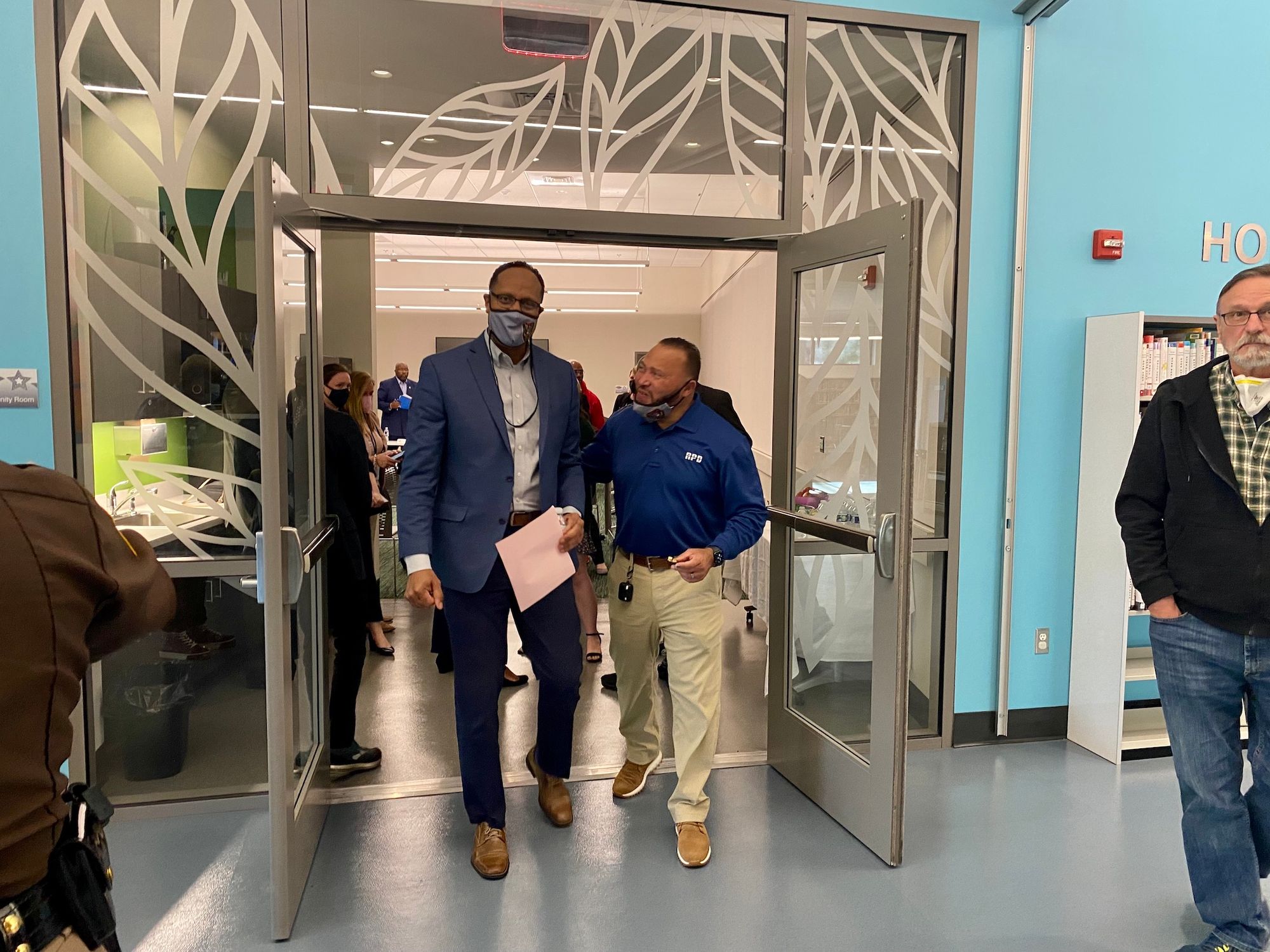

At the Melrose Branch Library, Virginia Sen. Tim Kaine presided over a roundtable talk last month about gun violence. Like cities across the country, Roanoke faces a recent increase in killings and shootings. Officials went around the table introducing themselves.

“I am a 30-year resident of this great city of ours,” Roman, 51, said, “and I am the chief of police.”

As the talk neared its end, Kaine said he would put Roman on the spot: What is different in Roanoke now than 30 years ago? How have the challenges changed?

“I think I have a very unique perspective and sometimes in environments like this, I really like to sit back and listen, which is why I've been so quiet,” Roman said. “So, for me, I’m a young African American male, I grew up in Brooklyn, New York, and really understand the symptoms of trauma, what trauma can do to a person in life.

“I’m a pastor in the community, and I’m the police chief,” Roman said. “Sometimes I suffer from identity crisis. I don’t exactly know who I am.”

As he said this, participants chuckled and Roman smiled. He was also being serious.

'The right person for the job'

The last day in March marked Roman’s two-year anniversary as Roanoke’s top cop.

From a once-in-a-century pandemic, to rising gun violence, 2020 protests for racial justice and a significant shortage of police officers, the past two years, Roman said, “have been unlike any other I’ve experienced in my 30 years in law enforcement.”

City Manager Bob Cowell tapped Roman back in March 2020, just as the coronavirus was threatening to upend society.

While Roman was serving as Lexington’s police chief at the time, he had long-standing Roanoke roots. He started his career at the Roanoke Police Department in 1992 and rose through the ranks to become a captain. He left for Lexington in 2017, a year after the city passed him over for the top job to appoint Tim Jones as chief.

The end of Jones’s tenure was rocked by remarks he made about rape victims and rap music that some interpreted as sexist and racist. In a city survey of about 700 residents on what they wanted in a next chief, some commented on that situation and others urged Roanoke to hire Roman, who would become only the city’s second Black police chief.

“Part of my decision-making in coming back to the city was largely because of the great men and women that work for this department, and I thought it to be an honor to really lead such talented people,” Roman said recently at his office in the police station.

Roman sat behind his desk and spoke softly; at times, the sound of rain hitting the roof almost threatened to drown out his voice.

City leaders describe Roman as thoughtful, analytical and composed.

“He's very calm and measured,” Councilman Joe Cobb, who chairs the city’s Gun Violence Prevention Commission, said. “I would describe him as an introvert, which, you know, many excellent leaders are introverts. They think very carefully before they speak, but they're also very calm in times of crisis.”

There is also another side to Roman — a charismatic and fiery Roman. That side is apparent when he ministers at Faith & Hope Church in Northwest Roanoke alongside his wife, Sonya, who manages the city’s emergency dispatch center.

Cobb, who is also a minister, described Roman as “a deeply spiritual man,” and said he believes it’s Roman’s “resilient spirit” that keeps him going in such a high-stress profession.

Mayor Sherman Lea said Roman’s faith allows him to connect with people from diverse walks of life.

“He’s the right person for the job,” Lea said. “I was impressed when we had the demonstrations, or protests, rather, back a while ago with Black Lives Matter. … He would go out and talk to people right across from the police station. … And that’s him, and I think his leadership in the church helps him do that. … If I’m in the trenches, fighting a battle, I want a person like him on my side.”

From racial profiling to racial justice

Roman grew up in the 1980s in Brooklyn, New York, “where the crack epidemic was at its height,” he said. Roman described his parents as “blue-collar workers” who provided “enough leadership in the family to make sure that I stayed on the straight and narrow.” His father worked at a shoe company. His mother worked in the daycare and kindergarten realms as a teacher.

Roman said he experienced good and bad encounters with law enforcement during his childhood. Police officers stopped him many times on his way to play basketball in the neighborhood park.

“I guess someone who looked like me fit the stereotype of those who are involved in the drug market, either sales or user,” Roman recalled. “I didn't let the bad experiences that I had shape my opinion of law enforcement, because I knew that there were far more good officers than there were bad.”

He took the civil service exam and applied to the New York Police Department but was too young to become a rookie. He entered the U.S. Marine Corps. It was while stationed at the Quantico base in Northern Virginia that Roman discovered the Roanoke Police Department during a recruitment fair. At that point, he could have returned home and joined the NYPD.

“I was invited to come to Roanoke, take a look at the city, and I absolutely fell in love with it,” Roman said. “And 30 years later, here I am.”

In addition to the pandemic, the spring of 2020 proved a trial by fire for Roanoke’s new chief.

Protests over the May 2020 murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police spread worldwide. In Roanoke, hundreds of people on a sunny afternoon marched from a Washington Park rally to downtown, chanting slogans of peace and racial justice.

When protestors first attempted to get past a police line on Campbell Avenue near the police station, officers pepper sprayed some on the front lines. After talking to Jordan Bell, a community activist, Roman agreed the demonstrators could make their way up the street. The chief would later tell the media that police were concerned a small group was angling to vandalize the station.

Bernadette “B.J.” Lark, a community activist involved in the demonstration, was among those pepper sprayed by officers.

“I believe what they did that day was not at the orders of the chief,” Lark said. “At least, not the chief that I know.”

Lark said she came to know Roman from “being in fellowship” with him in church circles. She said the chief called her later to talk about what had happened. A week following the march, Roman walked alongside community members in another demonstration, she said. Lark stressed the marchers’ mission: “Our communities cannot afford the cost of violence, no matter who it’s from.”

“I believe he understood the pain of the community, I believe it was never his intent to hurt community members,” Lark said. “He’s just in a system like we all are. He’s trapped in a system and he’s trying his best to be a healing part of the system.”

Low morale and high crime

By the end of 2021, the trauma of the preceding year had taken a toll on the police department.

About 70 officers said their morale was lower than it was a year before, according to a survey of 105 employees obtained from the city that was conducted by the Roanoke Police Association, the department’s de facto union.

Just as many officers said Roman had failed to meet expectations since he arrived as chief.

(The president and a past president of the association did not respond to interview requests for this story.)

Since the survey, Roman said the department is “in a better place,” and has held conversations with officers about lessons learned over the past year. Roman’s leadership has brought more education on Black history to the police academy, as well. Recruits are now visiting the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. and partaking in a walking tour of Roanoke’s Gainsboro neighborhood that Bell leads.

Roman pointed to external conditions — such as police reform laws at the state level and protests outside the station — as factors influencing officers’ morale.

“It was tough for the officers being spit at, it was tough for the officers standing on that yellow line in front of the building and looking at kids say very bad things to them with the approval of their parents,” Roman said, “and in many cases, those were the kids the prior week that we read to in our reading program both at West End Center and in various other places, so it was very demotivating for them. And I think, as a result, morale suffered.”

Like police departments nationwide, Roanoke’s has faced a severe shortage of officers. When Roman arrived, there were 247 available officers and 20 vacancies. Today, there are 209 officers available on force and 55 vacancies, according to the city.

In December, Roanoke City Council voted to boost police compensation in the latest round of bonuses. A police spokeswoman in an email described the move as “one of the most significant pay increases for officers in several years,” and that Roman was “honored that it occurred during his tenure as Chief of Police.”

Still, like other communities, Roanoke is facing a scarcity of police at the same time as it’s experiencing rising gun violence. Homicides and shootings have occurred more frequently in recent years amid the economic and social impacts of the pandemic.

In November 2020, the department established a full-time gang investigations unit. The team is fully staffed, a spokeswoman said, after hitting a speed bump earlier because of short staffing.

“It would certainly help if we had more officers on the street,” Roman said. “But it is certainly not the sole solution, nor does it mean we just throw up our hands and say we can’t control it.”

Lea has grown increasingly frustrated by the violence and his sense that “guns are creeping back into schools.” Late last month, police detained a student after he fired a gun in a middle school restroom. The week before, a school bus was hit by stray gunfire. (Nobody was injured in either case.)

Lea praised Roman for being engaged in the community. He cited Roman's involvement in the mayor’s summer basketball league, in which police officers play games with youth.

But the mayor said he would like the chief “to be seen out front” more at critical incidents. At the site of the school bus shooting, Roman did not appear to be present when TV crews were on scene.

“He has an approach that can soothe and calm the waters,” Lea said. “So at times, when there are things at schools, or you got the superintendent out, I would like for the chief to be there, because he has an ability to calm things down.”

'We bring the fire'

On Palm Sunday, two dozen people gathered inside Faith & Hope Church on Orange Avenue.

A white van parked outside advertised the presence of Pastor and Lady Roman. Inside, a drummer, organist and electric keyboardist played while singers gave praise to the Lord.

Roman came out of a back room and bounded to the stage, raising his hand and swaying to the music. He wore a pink collared shirt, gray sweater and jeans and a belt with a buckle in the shape of the Louis Vuitton logo.

“We want to be an anchor on this corner for our community,” he said as people walked to an offering pot. “We want to be part of the process to make the community better.”

During his sermon, Roman stood at a transparent lectern, paced the stage and wiped his brow with a washcloth.

“I have warned you before, amen, that the folks who go to this church are all felons,” Roman said with a grin. “Why do you say that…? Because we are all arsonists. We bring the fire.”

“You may ask me, what the fire is,” he continued. “The fire is the love of the Holy Ghost.”

Palm Sunday commemorates when Jesus rode triumphantly into Jerusalem on a donkey.

“For many years at the police department, I was on mounted patrol,” Roman said. “This six-foot-six dude from New York rode a horse.” Jesus could not do such a thing, the chief said, because He had to be on the same level as the people. Roman focused his sermon on the crowd surrounding Jesus. Who were these people? Praisers, skeptics, heretics, a traitor.

The lesson: Take assessment of your own crowd. There are people hoping you will fail. There is someone who will sell you out. But you cannot mind these sinners. You need to continue onward to your destiny, to stop worrying about the Judases in your life.

“They’ll sing your praises one day,” Roman said, “and kill you the next.”